Founding of the Metroplex: Arlington, Texas (Part 1 of 2)

Many years ago, Arista Joyner wrote a book titled Arlington: Birthplace of the Metroplex (published 1976). She could not have stated it any better or been more correct.

After reading a variety of reference material available on local history, both in print and online, I felt compelled to bring some of this information together from these multiple sources, and create a single document. The concept that I desired was to have one fairly easy to read document designed to provide the reader with a quick and solid summary of important local history leading up to Arlington being established.

The roles played by pioneers, soldiers, and Indians within the boundaries of what we now call the Arlington city limits were great and lasting contributions to the “Three Forks” region, presently known as the Dallas/Fort Worth Metroplex.

Archeologists have found evidence of hunters and gatherers in the area dating from about 9,000 years ago. It was the arrival of the white man in the form of westward settlers who left their mark on the Arlington area and the surrounding cities. The occasional settler had begun arriving in this area of the state in the early 1800s; primarily, it is the 1830s and 1840s during the westward migration where many of our local communities find their roots.

East and northeast Texas were locations where early settlers first began to inhabit. Locations like the town of Bonham and those in the Red River area had already-established military outposts. In the summer of 1839, the Texas militia, under orders from President Mirabeau B. Lamar, drove the Cherokee Indians from east Texas. As the Indians were pushed westward, some whites had already begun to settle in what had previously been Cherokee Territory, known as the Three Forks region of the Trinity River. Conflicts were certain to happen.

This area was prime with provisions of wild game and fish, as well as places to build homes and plant crops. All of these were attractive to the new settlers. Surveyors working for the Republic of Texas were already in the area by this time; however, they were liable to be attacked and killed at any time, as there were also plenty of Indian tribes in the region who did not appreciate the continuing encroachment on their lands.

Settlers often had the same terrible experiences with the Indians. They were killed, their animals and farming tools stolen, and homesteads burned to the ground. To combat the growing aggression by the natives, settlers joined companies of Minutemen, the title given to the volunteers authorized for frontier defense in the session of the Fifth Congress of the Republic of Texas. The act was signed in February 1841.

Following several Indian raids and killings in north Texas, settlers and Rangers alike felt something had to be done. The Minutemen gathered on May 5, 1841, at a camp known as Choctaw Bayou. The first order of the day was to organize into a military company and elect officers. Several of these men would later have cities, towns, and counties named for them. Some of those men were James Borland, William C. Young, John B. Denton, and Henry Stout. General Edward H. Tarrant of the Fourth Brigade, Texas Militia, was not elected to a command. However, as a senior officer, he was consulted on every measure, and before the expedition ended, he was in command. When members of the expedition wrote their memoirs 40 years later, they recorded the event as Tarrant's Expedition.

This expedition departed for the upper banks of the West Fork of the Trinity River near the present-day town of Bridgeport in Wise County. After several days of riding to this location, they found two deserted villages of 70 lodges. General Tarrant deemed it imprudent to burn the villages which were situated on a high hill, because the smoke would be seen for miles. Axes slashed enough destruction to make the villages uninhabitable. The first blow in the war of retaliation had been struck. With rising spirits, the Minutemen moved on.

From here they proceeded southeast toward the Brazos River, and then headed toward the Western branch of the Trinity River. Here a lone Indian was captured. Later, facing certain death, the brave relented and revealed the location of numerous Indian villages. The Militia, armed with this new information, was on the trail to an area now known as Village Creek. The expedition followed the north bank of the stream until they camped for the night.

The next day, they followed a trail to an Indian encampment on Village Creek, a short distance above where that stream is crossed today by the Texas & Pacific Railway between Fort Worth and Dallas. The creek served as a sanctuary for several Indian tribes who made frequent raids on frontier settlements. Numerous native encampments were found in this valley. Many of these camps were located south from the area where Lake Arlington is now situated, and north to its mouth on the Trinity River.

On May 24, 1841, Brigadier General Edward Hamilton Tarrant, whose men called him "Old Hurricane," led fewer than 100 men to Village Creek, where they engaged a larger Indian force, retreating after Captain John Denton and reportedly only 12 Indians were killed. As a result of the Battle of Village Creek, many tribes began moving west. General Tarrant returned to the battle site in July with 400 men but found the Indian villages had been abandoned.

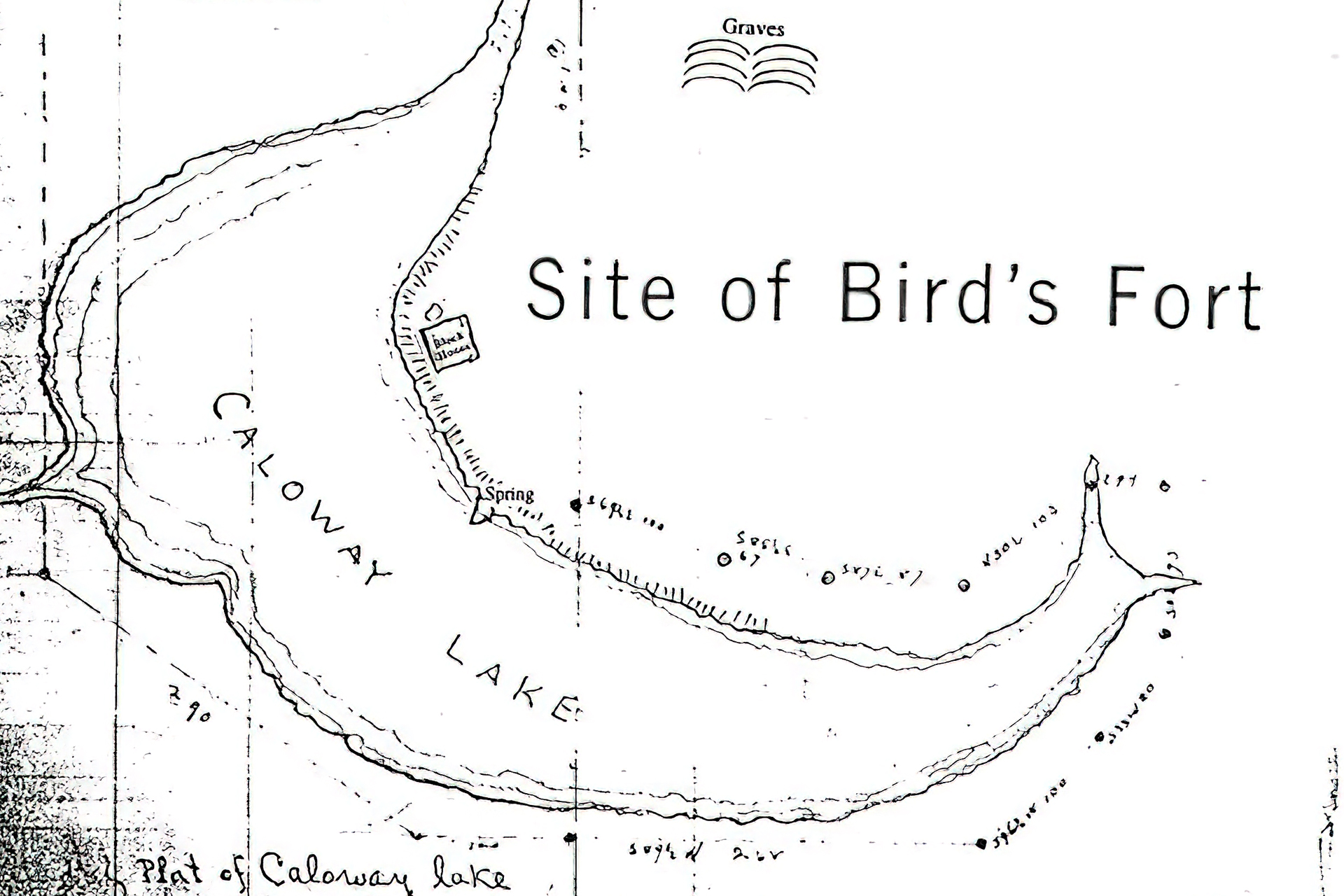

To further protect settlers in the region, General Tarrant ordered Major Jonathan Bird's Ranger Company to construct a fort in the area. Bird chose a spot to the northeast of Village Creek near the Trinity River. In the summer of 1841, Bird and his volunteers constructed their fort on the north side of a crescent shaped lake just east of present-day Highway 157.

Sam Houston visited Bird’s Fort and the surrounding area, hopeful of making peace with the numerous Indian tribes in order to protect the continuing influx of settlers. Houston held Grand Councils with chiefs from various tribes in the area. A treaty was soon reached, which was beneficial to both the Republic of Texas and the tribes. The chiefs were presented numerous gifts from the Republic.

A Treaty of Peace and Friendship between the Indians and the Republic of Texas was partially signed at Bird’s Fort, and finalized on September 29, 1843. Some of the chiefs held the fear that an ambush was awaiting them at Bird’s Fort and did not attend. Many references indicate that the treaty was initiated at Bird’s Fort, and that final signatures of the chiefs were obtained at Grapevine Springs and Marrow Bone Spring with representatives of Sam Houston and the remaining tribal chiefs.