General Edward H. Tarrant and the Men Who Rode to Village Creek

(This article includes popup citations—to read a citation, simply click on a citation number.)

The seventy men rode in the semblance of a military column through the north Texas prairie, the grass tall and still green from the spring rains. However, the men's clothing displayed no semblance of military uniform. They wore coats, vests, shirts, and breeches of homespun cotton or wool in a variety of colors, prints, and patterns. A few may have dressed in buckskins, stained and hardened from age and exposure. A surprisingly large percentage of the men wore boots, for there were a great many prominent men riding in the column. The less affluent wore brogans or moccasins.

Their headgear ranged from beaver slouch hats to cheap woolen plug hats. Some may have worn militia caps or Mexican sombreros, the wide-brims providing protection from the glare of a late Texas May.

Most of the men had armed themselves with Kentucky long rifles in either flintlock or percussion. Others favored shorter, double-barreled shotguns. Some had single-shot horse pistols thrust into their belts. A few—the very elite—may even have carried some of Samuel Colt's new-fangled five-shot revolvers.

Even Brigadier General Edward Hampton Tarrant, riding at the head of the column, seemed more like a back woodsman than a professional soldier. In fact, the general was one of the few men in the procession who belonged to the regular army of the Republic of Texas. The rest were mostly volunteers, militia, or, as they were sometimes known, Texas rangers.

The night before, the expedition had camped on the north bank of a narrow, murky river some fifteen miles below the confluence of its West and Clear Forks. About the same distance further downstream the Elm Fork emptied into the main channel. Between those confluences the river flowed almost due east, but below the Elm Fork it veered to the southeast and held that general direction for the rest of its lengthy course before finally draining into the Gulf of Mexico. Spanish explorers a century and a half earlier had named it La Santisima Trinidad. Later Texians had anglicized and abbreviated the name to the Trinity River.

After breaking camp that morning the column had ridden toward the rising sun. Soon they had struck an old buffalo trail that led down a draw and diagonally across a natural ford in the river. There, in the soft sand of the riverbed, horse tracks could be discerned among the forked hoof prints of the bison.

Had the tracks been left by a wandering herd of mustangs? Or had they been made by Indian ponies, perhaps by the same raiders that had massacred the Ripley family six weeks earlier?

While the rest of the men watered their thirsty mounts, General Tarrant dispatched six scouts to follow the trail that continued on the south bank of the river.

Captain Henry Stout, a crusty forty-two-year-old frontiersman, led the scouting party that loped away from the main column. Like most Texians of the Republic era, Stout's roots lay elsewhere. He had been born in 1799 in Logan County, Virginia, but while still a child had moved to Green County, Illinois.1

At the age of eighteen he left Illinois. During his journey south he successfully courted seventeen-year-old Sarah Talbot of Missouri. They settled briefly at "Salt Licks" in the Little River country of southwest Arkansas. There Stout worked as a hunter, supplying meat for James a Clark, who had a government contract to manufacture salt. When he had saved enough, Stout purchased a horse and brought his wife and new son, Ceylon, to Nacogdoches in the Spanish province of Texas.2

In June, 1819, Dr. James Long's filibustering expedition captured Nacogdoches, and Long declared the area independent from Spain. Four months later Spanish troops recaptured the town and drove the invaders back into the United States. To escape Spanish reprisal against the Anglo-Americans, Stout and his wife fled north to the undefended Red River valley, an area claimed by both Spain and the United States, but supervised by neither.

As early as 1811, traders and trappers, renegades, and runaway slaves had established an informal community among the ancient Indian mounds on the peninsula known as Pecan Point, which extended up from the south bank of the Red River. The first permanent settlers had arrived on the peninsula in 1816. There was never an organized town, but Pecan Point became the site of the first Anglo-American settlement within the modern boundaries of Texas. Stephen F. Austin would not bring his first colonists until 1821.

About 1817, Henry Jones established a ferry and home on the south bank of the Red River just west of Pecan Point. Although there is evidence that other Anglo-Americans had already established themselves in the vicinity, the settlement became known as Jonesborough.3

Ignoring Spanish claims, these Red River settlers generally considered themselves residents of the United States. In 1820 a significant portion of present day northeast Texas was incorporated into newly created Miller County, Arkansas.4

Stout grew with the region. By 1821, only two years after he had settled there, he had acquired some 4,400 acres. Two years later James Clark arrived in Jonesborough with a commission from General Andrew Jackson to supply the Chickasaw and Choctaw tribes that were being forcibly removed to the Indian Territory. Clark encountered his former employee, Henry Stout, camped at a spring just below Pecan Point. Clark purchased the surrounding land from Stout and founded Clarksville, which quickly grew into the largest town in the region.

Stout also developed a formidable reputation as a frontiersman and Indian fighter. Judge Pat B. Clark, grandson of James Clark and a prominent citizen of the Red River country, related an episode that occurred when Stout was scouting alone in the upper Trinity frontier:

An Indian had hidden in a small thicket of dogwood bushes and as Henry Stout rode up the Indian rose and shot his arrow. Stout wheeled off his horse, but the arrow with a flint-rock head went through his buckskin trousers and embedded itself in the thigh of his left leg so deeply that with all his strength he was unable to pull it out. He was afraid to cut it out with his knife for fear he would sever a blood vessel and bleed to death. He cut the arrow down close to his leg to keep down the vibration which would aggravate the wound. He then mounted his horse and turned toward Ft. Towson, a distance of approximately 180 miles and procured there the services of an army surgeon, who cut the arrow head out of his leg.5

Judge Clark did not date this incident. However, during his career Henry Stout frequently penetrated the wilderness surrounding the forks of the Trinity. Indeed he may have known that region as well as any white man.

Thus Stout had been a logical choice to lead the scouts on this current expedition into the upper Trinity. At the age of forty-two he was still fighting Indians.

If he could find them.

The six men rode for several miles across the prairie. Then the buffalo trail cut into the dense forest of the eastern cross timbers. This strip of post oak woodlands, ranging from two to fifteen miles in width, descended vertically from the Red River, bisecting both the West and Elm forks of the Trinity. Its dense foliage provided a natural haven for wildlife—and for Indians.

Other expeditions, both larger and smaller, had penetrated this same wilderness amid the forks of the Trinity. Stout had scouted for some of them. But always, unseen eyes had discovered the presence of the approaching intruders. The expeditions had found only abandoned villages, the Indians having disappeared into the dense woodlands or evaporated out on the vast prairie.

The scouts rode silently along the trail through the forest, their eyes scanning the foliage, their ears tuned to the rustle of every branch, the chirp of every bird. The trail drifted toward a brush-covered rise in the ground. The scouts halted there behind the rise and peered through the covering undergrowth.

The rise formed a natural levee for a small creek that meandered north back toward the river. In a clearing on the opposite bank, a squaw tended the fire beneath a copper kettle. Beyond her, Indian lodges hid in the shadowy trees.

Although Stout could not distinguish any other movement through the dense foliage, he knew the Indians would not abandon their women.

The village was occupied!6

Stout whispered instructions to his scouts. Ride back to the main column and bring it up as quickly as possible. He would wait there and keep watch. For the first time in the history of this region, a Texian force would attack an occupied Indian village in the forks of the Trinity.

Tarrant's expedition had originated at Choctaw Bayou on the Red River. The Red River settlements in the north formed the thinnest and most vulnerable terminal of the crescent of Anglo-American population in Texas. This crescent thickened as it moved down the Republic's eastern boundary and then spread out along the coastal plain to the south. This semi-circle of Anglo settlement curved around a wilderness that stretched westward to the Red Fork of the Brazos. At its heart were the three forks of the Trinity.

Traditionally the region had been the domain of the Wichitas, a tribe that straddled a line, both geographical and cultural, which separated the agricultural tribes of east Texas from the nomadic plains Indians of the west. Though primarily farmers, the Wichitas had adopted the horse into their culture and galloped onto the prairies in pursuit of bison.

However, the Wichitas had accommodated other tribes into their wilderness refuge, including their cousins, the Caddoes. Perhaps the most sophisticated of the east Texas agrarian tribes, the Caddoes had warmly welcomed the first Spanish missionaries. The Spanish came to know them as the "Tejas," a corruption of the Caddo word "tayshas," which meant "friend" or "ally." Indeed, the Caddoes most enduring contribution to Texas history would be that they gave the state its name.

Ironically, they paid a bitter price for that privilege. Along with God, the Franciscan missionaries introduced the Caddoes to European diseases for which the Indians had no natural immunities. Epidemics swept through the tribes claiming three thousand lives, perhaps half the population of the Hasinai nation.

A similar fate had befallen the Bidais, who regarded themselves as the oldest natives of Texas. European diseases had almost exterminated the tribe; by 1830 there were only about a hundred men left.7 They followed the Caddoes to the forks of the Trinity.

Fragments of the Cherokee, Creek, and Seminole, three of the "five civilized tribes" forcibly removed from their homes in the southern states, also settled in the region. There, too, came Delaware, Kickapoo, and Shawnee Indians, remnants of tribes shoved out of the northeastern United States.

The wilderness drained by the three forks of the Trinity became a refuge for displaced Indians. Since many of the Indians had come to Texas from the United States, they became known as the "emigrant tribes." Though the tribes were products of diverse geographical regions, their cultures shared certain similarities. They were generally farmers rather than hunters, more often products of woodlands rather than plains. And there was another similarity. Most of the tribes had been displaced from their native homes by the white man. Under such circumstances, even normally docile tribes became aggressive, joining in the raids against the Anglos, usually striking the nearest settlements along the Red River.

In 1836 Texas secured her independence from Mexico, and Sam Houston, the hero of San Jacinto, became the first President of the new Republic. As an adopted son of the Cherokee nation, Houston campaigned relentlessly to maintain peace between the Indians and the Anglos in the Republic of Texas. However, the Texas Congress opposed virtually all Houston's efforts. Sympathetic Indian agent Noah Smithwick wrote:

President Houston, having spent many years among the Cherokees, was fully alive to the situation, sympathizing with the native races, as have also learned to do, for the wrongs that had been done them and knowing that he was powerless to prevent it, that in spite of treaties, the conflict must go on till the Indian was exterminated or forced into exile.8

Smithwick told Houston that the Comanches desired a dividing line between their tribe and the whites. The president sadly shook his head and remarked, "If I could build a wall from a the Red River to the Rio Grande, so high that no Indian could scale it, the white people would go crazy trying to devise means to get beyond it."9

But public sentiment mounted against Houston's pacifistic Indian policies. There had been too many raids, and too many of them were attributed to the tribes encamped around the three forks of the Trinity. On September 3, vice-president Mirabeau B. Lamar was elected the next president of the Republic. Although Lamar would not take office until December, he had made it known during his summer election campaign that he strongly opposed his predecessor's conciliatory treatment of the Indians.

That same month, General Dyer raised a small company of forty-five volunteers to march against the Caddoes and other hostile tribes on the upper Trinity. Henry Stout and his brother, William, served as scouts on this expedition.10

When Dyer's expedition neared the Trinity, the Stout brothers rode ahead. Along the Elm Fork, they encountered eight Indians. The Stouts killed one brave, but the others escaped. The brothers separated to look for Indian signs. William Stout discovered some friendly Kickapoos who warned him that "the country was full of Caddoes."11

While the Stouts were away from the main column, Dyer's men captured an Indian brave. The captive claimed that there was village of hostiles on the Sabine and agreed to lead the a whites there. Captain William Scurlock and twelve men set out with the prisoner. They found the village, but it contained only eight Indians, "naked and singing." The Texians attacked and killed four of the Indians.12

The expedition disbanded shortly afterwards, but General Dyer was not satisfied. He had hoped for a significant victory over the Caddoes. Dyer, William Stout, and a half dozen others from the expedition joined up with a company of 70 men organized by Daniel Montague of Fannin County.

According to Stout, "They went high up the Trinity—but finding no enemy, on coming back came a upon a small encampment of the Caddoes on the Clear fork of the Trinity & killed three of them."13

Dyer also described the expedition in a report to Captain James S. Mayfield dated October 21, 1838:

The people are very much alarmed on our frontier. I have just returned from a campaign on the Trinity but owing to the season being so dry and the grass being entirely dry we were compelled to return. I sent the most of my men home and went with eighty men within two miles of the Caddo Village but could not make much discovery being on the most westerly fork of Trinity and destitute of provisions we were obliged to return. I could find but very few Indians. We had a skirmish with some Caddoes. We killed six and we had two men wounded.14

Even as Dyer described his inconsequential campaigns on the Trinity to Mayfield, two other generals in Nacogdoches were preparing an even more massive expedition into the three forks region.

Thomas Jefferson Rusk had signed the Texas Declaration of Independence and been elected first secretary of war of the Republic of Texas. During a skirmish the day before San Jacinto, Mirabeau Lamar had rescued Rusk from capture or death. After Houston assumed the presidency, Rusk resigned as secretary of war but continued to hold the rank of brigadier general in the army.

Hugh McLeod had served as General Rusk's aide during the early days of the Republic. A prolific writer, McLeod's letters provide a meticulous record of the largest Texian military expedition to penetrate the three forks of the Trinity.

On October 25, 1838, McLeod justified the new campaign in a letter to president-elect Lamar:

The time he [Rusk] says has arrived for a general, prompt & vigorous campaign against the Indians... At every hour we hear of fresh depredations, and each petty success leads to bolder efforts. It may do for those at a safe distance who have no interest at stake to prate the sickly sentiments of a mistaken humanity, but the man whose cabin is in ashes, whose family are wanderers and himself hunted down like a wild beast, must answer blow by blow, and take blood for blood.15

According to McLeod, General Rusk was organizing a three-pronged campaign to exterminate the hostiles. General Moseley Baker would march up the Trinity from the south, General Dyer would march southwest from the Red River, and General Rusk would march east from Nacogdoches, all converging on the frontier that surrounded the upper Trinity and Brazos rivers.

In a letter to Lamar dated November 16, 1838, McLeod described a delay in the expedition:

The General [Rusk] then called upon the officers, to raise 300 men, out of 500 then in the Army, and march to three fork of Trinity, & destroy the villages of the wild Indians, but 45 men were willing to go. We are all without commissions, and had no means of forcing them.16

McLeod closed the letter blaming Houston for "the damnable Indian policy (that) has produced all these difficulties."17

On the next day, General Rusk himself wrote to Lamar. After congratulating the president-elect, Rusk urged the Texas Congress to organize a permanent force of five hundred men, mostly infantry, to operate against the Indians. "I shall leave here in few minutes for Red River accompanied by Gen'1 McLeod." wrote Rusk, "My object will be to raise there a sufficient force to ... destroy the villages of the enemy on the Trinity."18

However, Rusk and McLeod detoured to Port Caddo, Louisiana, to confront hostile Caddoes there. On November 21, McLeod wrote Lamar:

Brig Genl Dyer rendevoused several days since at Clarksville with 400 men, for campaign against the Indians on Trinity & Cross Timbers—we will join him in a few days—He (Genl D) detached a company of 40 men to this vicinity under Capt Tarrance with orders to destroy a band of Caddoes (60 men) camped near here—and if necessary ... to follow them across the line & exterminate them—Those Indians have been making incursions into Texas & retreating to the U.S. for protection.19

The "Capt Tarrance" to whom McLeod referred was Edward H. Tarrant, an increasingly prominent figure in northeast Texas. He had been born in South Carolina in the mid-1790's.19 While Tarrant was still an infant, his father, Samuel, relocated the family to Montgomery County, Tennessee, where he died soon after. Tarrant's mother, Elizabeth, returned the family to Greenville County, South Carolina. Later she married Jesse Cobb, and the family moved to Caldwell County, Kentucky.

Tarrant began his military career on November, 20, 1814, when he enlisted as a private in Captain Alney McLean's infantry company, 14th Regiment, Kentucky Detached Militia. Flatboats carried his company down the Mississippi in time to join Old Hickory behind the cotton bales at New Orleans.21

Tarrant was promoted to corporal on February 6, 1815. Later that year he left the military to practice law. On August 7, 1816, he married Polly Young of Caldwell County22 The couple moved to Henry County, Tennessee, where, during the 1820's, he was elected Colonel of Militia and later sheriff. The 1830 census reveals that he had relocated to Lexington, Henderson County, Tennessee. In 1832, he was appointed to a commission to restore the Henderson County courthouse, and he also served as the first clerk of the circuit court there, his term expiring in 1836.

However, by November, 1835, Tarrant had migrated to Texas, establishing his new home near Clarksville in Red River County. There are no records of his participation in any of the battles of the Texas revolution. Perhaps he had returned to Tennessee to conclude his business affairs during the struggle for independence.

In December, 1836, Tarrant was selected the first Chief Justice of Red River County, and in September, 1837, he was elected to the Texas House of Representatives. During his brief stay in the Second Congress, Tarrant served on the three-man committee (with Dr. Daniel Rowlett and Collin McKinney) that proposed the creation of a new county from the western portion of Red River County. The committee suggested the name Independence, but Patrick C. Jack argued successfully that the new county should be named in honor of the fallen commander at Goliad, Colonel James Walker Fannin.

Tarrant resigned from the legislature on December 12, 1837 and returned to north Texas to pursue his farming interests. He also developed a successful law practice. As hostilities with the Indian tribes increased, Tarrant was elected captain of local militia. He ultimately earned a reputation as an Indian fighter that resulted in the nickname, "Old Hurricane."23

Warned of the approach of Captain Tarrant's force, the Caddoes fled into a cane break near Shreveport on United States soil. Without hesitation, Tarrant pursued the Indians across the border. On November 23, McLeod wrote Lamar that he and Rusk were going to join Tarrant's company. "It will be a bloody affair, as the numbers are about equal, the Indians well armed and desperate. If I fall, Please write to my mother, & send her the years' pay that is due me."24

The bloody battle never materialized. As the Texian force drew up opposite the Indian encampment, the Caddoes called for a parley. Rusk demanded that the Indians either surrender their arms or fight on the spot. The Caddoes were reluctant. They were hungry, and their chief argued that without weapons for hunting they would starve. Rusk agreed to furnish them with provisions on the condition that the Indian band remain in Louisiana.

McLeod described the episode in yet another letter to Lamar, and then noted:

So stands that matter, but you must understand these are not all the Caddoes, by far the larger portion of the tribe, under Tarshar, the Wolf, are among the wild Indians of Texas, at the three forks of Trinity.

We start immediately for three Forks, the Fourth Brigade under General Dyer will have 400 men ready as soon as we get there at Clarksville. Let us drive these wild Indians off and establish a line of blockhouses, and we have done all we can now.25

For some reason, Dyer did not wait for Rusk and McLeod. In early December he led the Fourth Brigade out of Clarksville. Five wagons pulled by teams of oxen carried provisions for the campaign.

Rusk, McLeod, and the soldiers in their command marched day and night to catch up with Dyer's expedition. One night in early December, on the prairie about twenty-five miles west of Clarksville, something in the darkness spooked McLeod's horse. Unprepared for the startled animal's lunge, McLeod was severely "ruptured" and unable to proceed. Rusk left thirty men to protect McLeod. Then the general continued on, hoping to intercept Dyer's column at the head of the Trinity's Elm Fork, some eighty miles from the reported location of the hostiles' village.

McLeod recuperated at his prairie encampment for three weeks. The weather was bitterly cold, and the small force of men refused to announce their position by lighting campfires at night. A company of volunteers under "Judge Tarrant, the chief justice of the County, and a brave and patriotic man," also hurrying to join the expedition, paused at McLeod's camp. Not yet able to travel, McLeod instructed Tarrant "to halt on the extreme frontier, where the late murders were committed" and then send back two riders to guide McLeod's party. On December 20, McLeod scribbled to Lamar: "From the depredations by small parties of Indians lately, on the settlements above here, I fear the Indians have ascertained his [Dyer's] strength, and broken into squads to commit mischief, declining a general engagement."26

McLeod added that Tarrant's two riders had arrived at his camp the previous night, and he was leaving for the Trinity immediately. "We have a good pilot, plenty of provisions, & stout hearts If we are not in time for the main battle, we may pick up a 'chunk of a fight' with a straggling party."27

McLeod apparently caught up to the Fourth Brigade at the Clear Fork of the Trinity. No Indians had yet been located, and supplies were dwindling. Apparently Tarrant was ordered back to the Red River to collect a herd of beeves and other provisions for the column. Rusk left some of his troops to guard the wagons and baggage at the encampment and then marched into the cross timbers. He found Caddo villages, but no Caddoes. As McLeod had feared, the Indians had discovered the approaching expedition and fled from their homes, disappearing into the wilderness. Rusk burned the empty villages.

A band of friendly Kickapoos claimed that there were hostiles camped along the Brazos. Rusk drove his command westward across a frozen, desolate prairie. They forded the Red Fork of the Brazos, but found no trace of the Indians. Hungry and discouraged and exhausted, the column to fell back to the Trinity.

Provisions were critically low at the camp on the Clear Fork of the Trinity. Tarrant had not returned with the supplies. On December 28, he had purchased one hundred and eighty bushels of fodder from Andrew Thomas at Fort Inglish, but he was then unable to procure the beeves.28 In desperation, Rusk ordered the wagons abandoned; the oxen that pulled them were killed for food. Then the Fourth Brigade began a weary retreat back to the settlements and disbanded.

The great expedition to the three forks of the Trinity had ended. Not a single hostile Indian had been killed.

On January 9, 1839, at a camp sixty miles below Clarksville, both Rusk and McLeod dispatched letters to President Lamar. McLeod wrote, "We are recruiting our broken down horses, and equally exhausted selves, after a march in my opinion, unparalleled since De Soto's." It was an interesting, somewhat glorified, exaggeration, which unintentionally conceded that the mighty Fourth Brigade had enjoyed no more success than the Spanish expeditions that, three centuries earlier, had vainly sought lost cities of gold. However, despite his fatigue and frustration, McLeod was able to muster enough enthusiasm to praise the land he had seen:

That Section of Country and particularly the Cross timbers (frequently represented as a sterile waste) is the finest portion of Texas as a body—and its bottoms are equally as fine as the Brazos.

We saw large droves of buffalo & wild horses, by the I latter I do not mean Mustangs, such as are found in western Texas—The Ukraine cannot excel these prairies in the beauty & fleetness of its wild horses.29

Rusk also was "worn down and exhausted." An official report would follow in several days, he wrote Lamar. He briefly outlined the route taken during the campaign. "I ascertained that the main body of the enemy were located high up on the Brazos and had not our provisions given out, we should have been able to reach them."30

Nine days later, in Nacogdoches, McLeod had barely recovered enough to rationalize about the campaign. "I will come down in a few days with Gen Rusk, but I am really so 'used up' now, that cannot undergo the fatigue—I've been riding so long, that I have almost become a centaur. He blamed the Kickapoos for misdirecting Rusk to the Brazos. The hostiles, McLeod argued, had been camped back on the Trinity.

Captain William B. Stout returned to the three forks of the Trinity in May, 1839, and located the five wagons abandoned by the Rusk Expedition. The Indians had removed all the iron parts and chopped on the wood frame with their tomahawks and hatchets. Somehow, Stout got the wagons back to the settlements, removing the last traces of the Fourth Brigade's campaign.

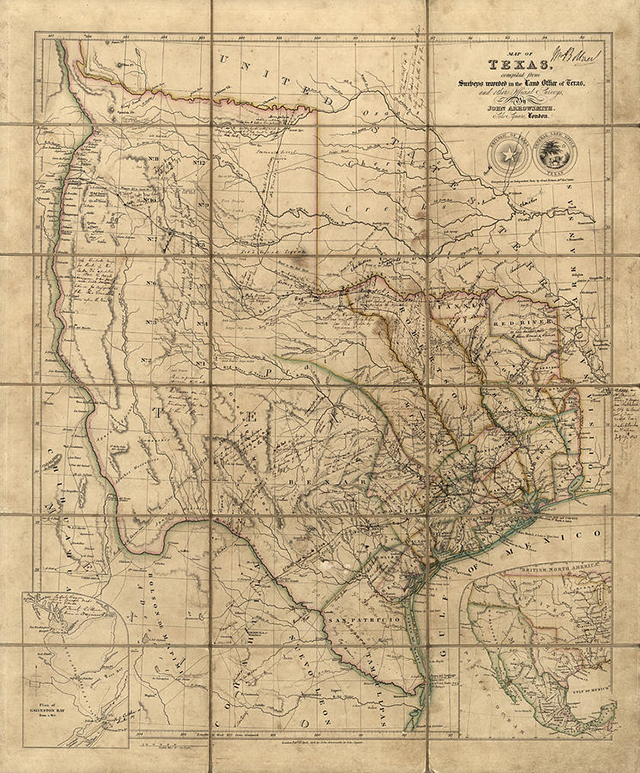

In 1841, John Arrowsmith, a noted cartographer in London, England, published a map of the Republic of Texas. The route taken by the Rusk Expedition was depicted in a dotted line.31 Otherwise, the campaign slipped into historical obscurity.

On December 10, 1838, shortly after the Fourth Brigade had left Clarksville on its futile march to the Trinity, Mirabeau Bonaparte Lamar became the second president of the Republic of Texas. Diametrically opposed to Houston's conciliatory Indian policy, Lamar advocated the extermination or expulsion of the tribes in Texas. During his administration the Republic erupted in a savage war for survival.

Born in Georgia in 1798, Lamar came to Texas in 1835, enlisting as a private in Sam a Houston's army. An act of gallantry on the plain of San Jacinto initiated his meteoric rise in Texas politics. During a cavalry skirmish on the day before the battle, Secretary of War Thomas J. Rusk was cut off and surrounded by Mexicans. Private Lamar galloped through the enemy troops, opening a path of retreat for Rusk. Then Lamar wheeled and shot a Mexican lancer who had unhorsed and wounded nineteen-year-old Walter P. Lane. The youth swung up behind another Texian cavalryman and escaped. As a result of Lamar's heroism, Sam Houston gave him a battlefield promotion to the rank of colonel in command of the Texian cavalry. After the revolution, Lamar was further promoted to major general and commander-in-chief of the Texas army. He served as secretary of war under David G. Burnet and vice-president under Houston.

President Lamar defined his Indian policy on December 21, 1838, in his first address before the two houses of Congress:

The Indian Warrior in his heartless and sanguinary vengeance recognizes no distinction of age or sex or condition. All are indiscriminate victims to his cruelties. The wife and the infant afford as rich a trophy to the scalping knife as the warrior who falls in the vigor of manhood and the pride of his chivalry... If the wild cannibals of the woods will not desist from their massacres; if they will continue to war upon us with the ferocity of Tigers and Hyenas, it is time that we should retaliate their warfare, not in the murder of their women and children, but in the prosecution of an exterminating war upon their warriors which will admit of no compromise and have no termination except in their total extinction or total expulsion.32

Lamar's speech focused on the emigrant tribes, especially the Cherokee, denying them "legal or equitable claim to any portion of our territory."33

One of the first military victories of the Lamar administration was the defeat of the Cherokees in east Texas. At the battle of the Neches, July 15-16, 1839, Texian forces routed the tribe. The survivors retreated north. Some took refuge beyond the Red River. Others settled in with their Cherokee brothers and the other displaced tribes amid the three forks of the Trinity. Once the most peaceful of tribes, the Cherokee now joined in on raids up to the Red River settlements.

They frequently struck around the Dugan homestead on Choctaw Bayou in modern Grayson County. Arkansawyer George S. Dugan had come to Texas in 1835 to select the site for his family. His father, Daniel Dugan, brought the family to their new Texas home the following spring. During an 1840 Indian raid, Daniel Dugan and a companion were killed and scalped while chopping wood away from the cabin.34 Later Indians attacked the Dugan cabin. A young visitor, William Green, was killed in his bed, and Hoover P. Dugan was wounded before the raiders were repelled.

In March, 1841, a war party of about fifteen braves raided along the Sulpher Fork in Lamar County. Captain John Yeary, an Arkansawyer who had entered Texas two years earlier, his son, and a slave were weeding a field about three a hundred yards from the farm house. His wife and daughter were in the house. It was a warm spring day and the front door was open. Yeary's daughter spotted the raiders when they were only twenty yards from the house. She slammed the door and bolted it. The Indians galloped up to the porch, leapt from their ponies, and attempted to force the door.

The war cries alerted Yeary, his son, and the slave. Armed only with their hoes, they dashed for the house. The warriors turned and met them at a fence thirty feet from the house. Captain Yeary, "a man of extraordinary muscular power," and his slave both waded into the Indians, frantically swinging their hoes. In the close quarters, the warriors had difficulty drawing their arrows, and instead used their bows as clubs. Yeary received a bloody gash above his eye, inflicted by either a blow or a grazing arrow. The slave also was wounded. Two of the Indians, armed with rifles, fell back and attempted to shoot at the settlers, but both their weapons misfired. Year's wife and daughter suddenly raced from the house, each carrying a rifle. An arrow grazed Mrs. Year's arm and another struck her in the hip. Captain Yeary bounded over the fence and took the rifle from his wife. Simultaneously, the daughter, who also had received a slight wound, passed another rifle to her brother. When Yeary and his son turned their weapons on the Indians, the small war party fled.

Fearing a return of the raiders, Yeary dispatched his slave to the residence of Elbert Early, five miles to the east. William H. Bourland, who was visiting Early, mounted up and followed the slave back to Year's cabin. Bourland reported:

The fight had been a bloody one indeed, the arrows was lying thick when I reached the Battle ground. The Indians made their escape, and owing to a very severe rain falling that evening, prevented us from capturing any of them. Capt. Yeary was strongly solicited by his family and friends to leave the frontier, but he refused. He has kept his ground, and is now living in peace, not dreading the approach of Indians—35

Less fortunate were the Ripley family. Their cabin stood along the Cherokee Trace about fifty miles below Jonesborough. On April 10, 1841, Ambrose Ripley was away from the farm. His twenty-year-old son was plowing in the field when a raiding party suddenly charged out of the trees. The young man fell, his body pierced by arrows and bullets. The warriors galloped on toward the farmhouse. The war cries, the screams of the dying son, and the gunshots had aroused the household, but there was no time for a defense. Abandoning her sleeping infant, Mrs. Ripley frantically hurried her other children out the door, instructing them to hide in a cane break two hundred yards away. The eldest daughter, sixteen years old, was shot down as she ran from the house. Mrs. Ripley and some of her younger children were overtaken and beaten to death with clubs. Only the second and third daughters, between twelve and fifteen years of age, reached the cane break and survived to relate the horrors of the massacre. The Indians plundered the house and then set it afire, leaving the sleeping infant to be consumed by the flames.36

As a result of these atrocities, volunteers began assembling at the Dugan settlement on Choctaw Bayou. On May 5, 1841 they elected their officers.37

The volunteers chose Captain James Bourland to lead the punitive expedition. Born in South Carolina in 1801, Bourland had moved first to Kentucky and then to Weakley County, Tennessee, where he had owned a racetrack and traded in both horses and slaves. He had arrived in Texas only the year before and worked as a surveyor.

Twenty-nine year old William Cocke Young was elected first lieutenant. A native of Davidson County, Tennessee, Young had settled at Pecan Point in 1837, becoming the first sheriff of Red River County that same year.

The men appointed Sam Johnston to the rank of second lieutenant. They chose Dr. Lemuel M. Cochran as orderly sergeant and McQuincy Howell Wright second sergeant. William N. Porter, a lawyer from Bowie County, served as Acting Brigade Inspector and later provided an official report of the expedition.

John M. and William H. Bourland, brothers of Captain James Bourland, had enlisted. William Bourland was the man who had ridden to the aid of the Yeary family. Captain John Yeary was there, eager to avenge the attack on his home. So was his neighbor, Elbert Early. And George Dugan enlisted to avenge the Indian attacks on his homestead.

The total number of men in the expedition numbered about eighty. Captain Henry Stout, ready to guide yet another expedition into the region, was assigned as one of the scouts for the campaign. Two other scouts, both Trinity veterans, volunteered. Claiborne Chisum had migrated to Red River County in 1837 with his wife and teenaged son, John Simpson Chisum (later to become the famous "jinglebob" cattle baron of New Mexico). Brigadier General John H. Dyer had designated Chisum and James R. O'Neal to head six-man scout companies forewarning settlers of Indian raids. In early June, 1838, both Chisum and O'Neal had led their companies into the forks of the Trinity. Now they were ready to return.

Mabel Gilbert, a steamboat captain from Tennessee who had settled two miles below Fort Inglish (later Bonham), also signed up, as did three brothers, John, Lyttleton, and Wade Hampton Rattan. Also present were Holland Coffee and Silas Colville, partners from Fort Smith, Arkansas, who had established Coffee's Station, a trading post on the Red River. Colonel Coffee was a remarkable man who had mastered at least seven Indian languages. He became one of the most prominent and popular figures in north Texas, representing the region in the Third Congress of the Republic.

Other notable figures in Texas history may also have accompanied the expedition. William B. Patton, who operated the only blacksmith shop and mercantile store between Paris and Clarksville, was probably there. Patton was a nephew of David Crockett. On a the plain of San Jacinto, he had avenged his famous uncle's death.

Family tradition places Isaac Parker on the campaign. He was the uncle of John and Cynthia Ann Parker, who had been captured by the Comanches during the massacre at Fort Parker in 1836. Born in Elbert County, Georgia on April 7, 1793, Parker had come to Texas in 1833. He had served with Elisha Clapp's company during the Texas Revolution. Prior to the Village Creek campaign, Parker had represented Houston County in the Texas Congress.

Daniel Montague may also have joined Tarrant. Born on August 22, 1798, in South Hadley, Massachusetts, Montague had migrated to Louisiana where he had worked as a surveyor. In the fall of 1836, he had settled at Old Warren on the Red River. In partnership with William Henderson, he had opened a general merchandise store and had been appointed surveyor for the Fannin land district.

"There were many of the most prominent men in northern Texas in this company," wrote Andrew Davis, a thirteen-year-old orphan who was perhaps the youngest member of the expedition. Since he could not furnish his own horse, his Aunt Gordon had supplied him with a mule. In later life, Davis became a reverend in the Methodist church and left his own dramatic account of the expedition.

Also present were Edward H. Tarrant and John B. Denton, the two men whose names would become most closely linked with the Village Creek expedition.

Tarrant's inability to provide beeves for the Rusk-Dyer expedition had contributed to the failure of that previous campaign to the three forks of the Trinity, but the incident had not blemished "Old Hurricane's" popularity. On November 18, 1839, he had been elected to the rank of brigadier general of the Fourth Brigade. Because he had no jurisdiction over volunteers, he joined them in an advisory capacity. However, because of his rank and his prestige, he became recognized as the commander of the expedition.

However, John Bunyan Denton became the ultimate hero of the campaign. According to biographer William Allen, "Denton was five feet ten inches high, very erect; had black, slightly curly hair, a broad, high forehead; weighed one hundred and sixty pounds, of impressive mien, and bore himself in a way that denoted great energy."38

Denton was born in Tennessee on July 28, 1806. His mother passed away shortly after childbirth; his father died when he was eight.39 Denton and his older brother, William, were adopted by a family named Wells who took them to the Arkansas Territory. The Denton brothers received no formal education, but they were apprenticed to Jacob Wells to learn the blacksmith trade. However, because of his youth, Denton was generally relegated to the household chores.40 At the age of twelve, he ran away from the Wells family and found employment as a deck hand on a an Arkansas River flatboat.

In 1824, he married Mary Greenlee Stewart of Louisiana. His wife was welll educated, and she taught her husband to read and write. Denton joined the Methodist Church the following year, and for the next decade he roamed through Arkansas and southern Missouri serving as an itinerant minister. He developed a reputation a as a magnificent orator. Dr. Homer S. Thrall, who a wrote a history of Methodism, said, When Denton addressed the multitudes that flocked to hear him preach upon the sublime themes of the Gospel, his appeals were all but irresistible."41

In early 1837, Denton moved his wife and children to Clarksville, Texas.42 Unable to adequately support his growing family as a minister, he directed his oratorical talents toward the practice of law. After six months of study, he received a license to practice, and entered into a partnership with John B. Craig at Clarksville.

The lawyer-preacher was also a soldier. In 1838 and 1839, he led two campaigns against hostile Indians in the interior of the Republic.43 A muster roll in the Texas State Archives lists Denton as the captain of a company of thirty-two mounted volunteers under the command of Major Peyton S. Wyatt. According to the roll, the volunteers served from July 15 until August 15, 1839.

Despite his legal and military careers, Denton did not retire from the ministry. His legal practice often required that he travel to neighboring communities. When attending court in Warren, he would conduct religious services at the Dugan residence. An "Old Texan" recalled that Denton was chosen chaplain of a regiment, and left his mark as a pulpit orator, though he seldom spoke in a pulpit.

I shall never forget the occasion of one of his sermons. We were camped at the mouth of what is now called Denton Creek, at Hackberry Fort, and were gathered in the grove to listen to Denton's sermon. As he was rising to begin, Gen. Rusk, of Texas fame, walked into the crowd and took a seat. It was one of the preacher's happy efforts. He chained his hearers, and memorialized the woods around with some of the grandest natural eloquence that ever rolled from human tongue. Gen. Rusk was charmed. He had never seen the preacher, and asked... what little "thunderbolt" that could be. Said he had heard of the renowned diction of Clay, of Prentiss and of Webster, but that such a deluge of rounded a periods never met his ears before.44

In 1840, Denton declared himself a candidate from Red River and Fannin counties for the Congress of the Republic. Robert Potter defeated him by only half a dozen votes.

As a member of the punitive expedition against the hostiles, Denton shared command of the scouts with Henry Stout. Most sources state that Denton also served as Tarrant's aide during the campaign.

On May 14, 1841, the eighty minutemen started for the Trinity. Jack Ivey, "a man of mixed African and Indian blood," served as pilot, guiding the expedition westward along the old Chihuahua trail.45

No previous expedition had ever located an occupied village. Tarrant hoped to succeed where the others had failed. Rumors placed the Indians responsible for the recent depredations on the West Fork of the Trinity near present day Bridgeport.

After a few days' march, Holland Coffee, Silas Colville, and eight other men abandoned the campaign and returned to Coffee's Station. The reason for their departure has not survived.

The expedition continued westward, crossing the middle fork of the Trinity and entering the cross timbers. On May 19, they discovered fresh signs of Indians. The company turned southwest and found, on the West Fork of the Trinity, two recently abandoned villages, containing some sixty or seventy lodges. They did not appear to have been recently occupied. General Tarrant ordered the villages destroyed. Because they sat on high ground, he deemed it imprudent to burn them. Instead, the rangers used their axes, and a little perspiration, to chop the lodges down.

For the next two days, the expedition marched south. On the night of May 21, the company camped on the Brazos. There were still no traces of Indians, so in the morning, Tarrant led his command back toward the east.

On May 23, the expedition again struck the Trinity and proceeded downstream. Andrew Davis remembered that they sighted a lone Indian brave on the prairie not far from the present site of downtown Fort Worth. According to Davis, Tarrant divided his command, ordering the columns to cut off the Indian's path of retreat into the timber. The brave was captured. That night, the expedition camped in a secluded area at the junction of Fossil Creek and the Trinity. An interpreter questioned the Indian captive, trying to ascertain the location of his village. When the prisoner stubbornly refused to answer, the minutemen resorted to more extreme measures. Davis recalled the manner of persuasion:

(The Indian) was then placed with his back against an elm tree, his hands were drawn around the tree and made secure and his feet were then tied together and secured to the tree. Then twelve men with their guns were ordered to take their position before the Indian. The scene was an awful one in its solemnity to me and to all. The men were ordered to present arms. At this moment the alarmed and terror-stricken Indian became greatly excited and in great agony of spirit he cried aloud: "Oh man! Oh man!" While he did not utter the above words with distinctness, yet it was more like these words than any other. Gen. Tarrant sent Capt. Yeary with an interpreter to the prisoner to see if he would reveal anything, for prior to this he had been sullen and would not say a word. He was made to understand that if he would tell where the village was and how to find it he should not be hurt, and he made a full revelation of the whole matter and closed by saying, "We be friends." He was relieved, but kept under guard all night. After dark, Tarrant sent ten men under Henry Stout, who was ordered to go to the village, reconnoiter the same and select the point of attack and report by 4 o'clock in the morning. This was done and by daylight all were in motion under the guidance of our trusty pilot for the village, which was reached about 9 or 9:30 in the morning.46

However, in his report to Secretary of War Branch T. Archer on June 5, 1841, Acting Brigade Inspector William N. Porter made no reference to the captured Indian or to Stout's all night scouting mission. Nor did John Henry Brown, whose 1880 account was based on communications from four participants. According to Brown:

On the next day (May 24), near their camp, they found an old buffalo trail, leading down and diagonally across the river. ... On this trail they found fresh horse tracks, and followed them. Henry Stout then, as throughout the expedition, led an advance scout of six men. Nearing the camp referred to, they discovered an Indian woman cooking in a copper kettle, in a little glade on the bank of the creek. Seeing he was not observed, and being veiled by a brush-covered rise in the ground, Stout halted and sent the information back to Tarrant.47

The scouts galloped back to the main column and reported that the Indian encampment was three miles ahead. Tarrant spurred his men forward, leading them to a thicket within several hundred yards of the nearest Indian huts. The village seemed quiet, still unaware of the presence of the enemy. The squaw at the kettle had been joined by another woman with an infant. Most of the Texians could not see any other Indians. Young Andrew Davis either had a better vantage a a point, a better imagination, or a poorer memory than the other participating chroniclers of the campaign. He claimed, "From our position we could see the Indians passing about in every direction."48

There was no time to send out a scouting party to ascertain the size of the village or the number of warriors present. With every passing moment, the small band of Anglos risked discovery and the crucial loss of the element of surprise.

The men were ordered "to divest themselves of their blankets, packs, and all manner of encumbrances. ... "49 The company was formed into a line a and told the charge would commence in five minutes. Andrew Davis recalled "Old Hurricane's" brief address to his company.

When the time was out, Gen. Tarrant said: "Are you all ready?" The response was in the affirmative. Then Tarrant, in a low, yet a clear, distinct voice, said: "Now, my brave men, we will never all meet on earth again; there is great confusion and death just ahead. I shall expect every man to fill his place and do his duty."50

General Tarrant gave the command to charge. Spurs sank into horseflesh, the mounts lunged forward, and the minutemen thundered toward the village. According to Davis:

A level prairie about 300 yards wide lay between the command and the first huts. This distance was measured off in less than half the time I am in telling it. In a moment the sound of firearms, with a voice of thunder, rang out over the alarmed and terror-stricken inhabitants of that rude city of the wilderness. Tarrant and James Bourland, with Denton, led the charge, while every other man followed with the best speed his horse could make.51

Davis was riding the mule furnished him by his Aunt Gordon. The animal was slow, and he was among the last to reach the enemy.

The two Indian women and the child at the copper kettle were nearest the attackers. The squaws screamed and then raced down into the creek bed, momentarily obscured by the bank. Alsey Fuller and some of the minutemen chased after them, expecting to find warriors waiting in the creek. As their horses plunged down into the creek, Fuller spotted an Indian scrambling up the opposite bank. Fuller shot the fleeing figure before he realized that his victim was one of the two women. The other squaw and the child were captured.

William Porter's report stated concisely, "The village was taken in an instant."52 Surprisingly, there were few inhabitants, and they quickly scattered into the dense underbrush.

Some of the minutemen remained to guard the village. James Bourland led others, including John B. Denton, Lindley Johnson, Lemuel Cochran, and Elbert Early, to investigate a trail that crossed and then paralleled the creek.53 A mile or two to the north, they discovered the second village. Bourland divided his command, leading half to the right and sending Sergeant Cochran to the left, in an effort to outflank the Indians and prevent their escape. But the Indians of the second village had been alerted by the sounds of battle. They quickly retreated into the thicket on the far side of the village, and from the cover of the underbrush they offered a more determined resistance. Cochran and Early aimed their rifles at one retreating brave, but both their guns misfired. As the warrior raced into the creek, he turned and fired a hasty shot at Early, but his bullet missed.54 Andrew Davis described this phase of the battle:

As I passed the first huts I saw to my right a number of Indians. I fired into the crowd with the best aim my excited nerves would allow. In a moment our men came upon them from a different direction, and for a short time the work of death was fearful. It was here that my mule was shot from under me. I felt like I had lost my best friend. The air was full of bullets and I took a tree. In a moment, however, I saw a number of our men on foot, some of them from choice and others, like myself, because they could not help it. I left my tree and joined them. In less than an hour the village was cleared of Indians, and it seemed like the work of death was done.55

A third village appeared beyond the second, and some of the minutemen continued their attack into the next encampment. "Many of the horses having failed, the men ran towards the village on foot," wrote Porter "but the Indians having heard the firing at the second village, had time to take off their guns and ammunition and commenced occasionally to return our fire."56

Tarrant now had men spread along the creek from the first village to the third. He had no way of ascertaining casualties, and he must have realized that his scattered force was vulnerable to an organized counter-attack. He ordered his command to regroup at the second encampment and instructed them to replenish themselves with the dried buffalo meat that was found in some of the Indian huts. Andrew Davis described the condition of the men:

On roll call, it was found that not a man had been killed: a dozen perhaps had been unhorsed. Quite a number were hatless. As many as eight or ten were slightly wounded, but none in painful manner. Many had made narrow escapes from death, as their rent clothes abundantly testified.57

In his official report, William N. Porter described the enemy casualties: "The Indians had twelve killed, that we counted; and a great many more must have been killed and wounded, from the quantity of blood we saw on their trails and in the thickets where they had run."58

Porter's report supplied other pertinent details that served both to explain the ease of the victory and to justify the campaign:

From the prisoners whom we had taken, we learned that at those villages there were upwards of one thousand warriors, not more than half of whom were then at home. The other half were hunting buffalo, and stealing on the frontier. Here was the depot for the stolen horses from our frontier, and the home of the horrible savages who had murdered our families. They were portions of a good many tribes--principally the Cherokees who were driven from Nacogdoches county, some Creeks and Seminoles, Wacos, Caddoes, Kickapoos, Anadarkos, etc. We counted two hundred and twenty-five lodges, all in occupation, besides those they could see a glimpse of through the trees in the main village.59

Porter reported that the Indian lodges contained an abundance of rifles, powder, balls, flints, and sergeants' swords, "which we supposed they must have taken from the place where the regular army (the Fourth Brigade) buried a portion of their ammunition." The Indians also had a blacksmith shop, and "farming utensils of the best quality, except plows." Porter added that some of the lodges were equipped with feather beds.60

As the rangers regrouped and rested in the second village, Captain John B. Denton suggested sending out another scouting party. Tarrant was reluctant. The villages they had attacked and occupied were more extensive than he had anticipated. Tarrant must have realized that the surrounding woods were filled with Indians in numbers far exceeding his own modest force of seventy. He finally granted Denton's request on the condition that the scouts proceed with extreme caution.

Captain Denton led about ten men along a trail that extended northwest from the village. Captain Bourland and another ten men followed a trail to the northeast. About a mile and a half from the village the two trails converged, and the scouting parties were united. Bourland and Calvin Sullivan left the group to pursue some stray horses, one of which was wearing a bell. Denton led the remaining men further down the trail. They struck a much larger trail that crossed their path, extending west toward the hills and east back through the creek toward the main branch of the Trinity. The scouts followed the trail to the east. Visible through the trees beyond the creek loomed a fourth village that appeared larger than any they had yet encountered. The trail that led to the village narrowed as it descended from the woods and forded a horseshoe bend in the creek. To a seasoned Indian fighter, the ford must have appeared an ideal place for an ambush.

According to John Henry Brown, Denton recalled General Tarrant's admonition of caution and halted the scouts in the trees above the creek. But Henry Stout was impatient. He galloped to the front of the column and challenged Denton, 'If you are afraid to go in there, I am not!" Denton snapped that he would follow Stout into the infernal regions. Stout took the lead, with Denton, John F. Griffin, and the rest of the men following single file down the narrow path that led to the creek bed.61

The three leaders had ridden about thirty feet into the creek bed when a band of Indians opened fire from concealment in the underbrush along the opposite bank. Rifle balls struck Denton in the arm, the shoulder, and the right breast. His horse pivoted and charged back up into the trees, still bearing the lifeless body of the preacher/lawyer/soldier.

Stout had been struck in the left arm when the first volley was discharged. He wheeled his horse to the right and raised his pistol, but a ball struck the gun butt and slammed the barrel against his skull. Almost simultaneously, five rifle balls pierced his clothing around his neck and shoulders. Another ball grazed Griffin's cheek. The other scouts, still descending the narrow, wooded path, retreated back into the woods and escaped injury. Andrew Davis described the confusion and desperation that followed:

The scene of death and the moment of suspense was awful to endure. Capt. Yeary halloed at the top of his voice: "Why in the h--l don't you move your men out to where we can see the enemy? We will all be killed here."

The men began at once a kind of irregular retreat, and Capt. Stout had so far recovered from his shock, as to be able to say: "Men, do the best you can for yourselves. I am wounded and powerless."

About this time some one exclaimed: "Capt. Denton is killed." The shot was so deadly that there was no death struggle. He had balanced himself in his saddle, raised his gun and closed one eye, intending to deal death upon the enemy, when the death shock struck him. When his death was discovered his muscles were gradually relaxing and his gun, yet in his hand, was inclining to the ground.62

Fearful of being surrounded and massacred, the scouts left Denton's body in the underbrush and quickly retreated to the second village. General Tarrant feared that the Indians would mutilate Denton's corpse. He dispatched James Bourland with twenty-four men to recover the body. When Bourland's party arrived at the horseshoe bend, they found that the Indians had withdrawn and that Denton's body had not been disturbed. Bourland tied it to a horse and rejoined the main column at the second village.

The death of Denton demoralized the company and impressed upon General Tarrant the precariousness of their situation. He could not allow the Indians to discover how meager his force actually was. A formidable band of warriors would be able to cut off his path of retreat and massacre his entire command. The rangers gathered up stray livestock and anything they could carry and left the camp at five in the afternoon. Porter described the booty:

We brought in six head of cattle, thirty-seven horses, three hundred pounds of lead, thirty pounds of powder, twenty brass kettles, twenty-one axes, seventy-three buffalo robes, fifteen guns, thirteen pack saddles, and three swords, besides divers other things not recollected.63

According to Porter, "It was not the wish of Gen. Tarrant to take any prisoners." The captives, all women and children, were permitted to escape.64 However, Brown maintained that no prisoners had been captured other than the Indian woman and child taken at the outset of the fight.

Tarrant led the minutemen back to Fossil Creek, where they camped for the night. While the men slept the squaw abandoned her baby and slipped past the sentries, escaping into the darkness. Apparently Tarrant himself adopted the infant.

On the following day about 11:00 am, the expedition interred Denton's body "under the bank of a ravine, at the point of a rocky ridge, and not far from where (present-day) Birdville stands."65 Then they continued on, arriving at Fort Inglish five days later.

Almost Immediately Tarrant began preparing for a larger a expedition back to the forks of the Trinity. Between July 15 and July 20, 1841, more than four hundred men assembled at Fort Inglish. William C. Young was there, elected to the rank of colonel, and James Bourland was chosen lieutenant-colonel.

Simultaneously, General James Smith, commander of the militia at Nacogdoches, marched from that post with another sizeable force. The two armies were to converge on the Indian encampments at Village Creek.

But everything went wrong. After marching southwest for weeks, Tarrant could not find either the Indians or General Smith. Discouraged, he returned to Fort Inglish.

In the meantime, Smith's army arrived at King's Fort (at the present site of Kaufman) and learned that the Indians had assaulted that place on the previous evening. Smith followed the trail of the retreating raiders, camping near the present site of Dallas only a few months before the arrival of that city's founder, John Neely Bryan. As his men rested and savored the abundant honey that would give Honey Spring its name, Smith dispatched twelve scouts under Captain John L. Hall to locate the Indian village. Among the scouts was a buckskin-clad surveyor from Tennessee named John H. Reagan, who would later become the Postmaster General of the Confederacy and a member of both the U. S. Congress and Senate.

The scouting party entered the cross timbers and found the village, its Indian occupants peacefully and unsuspectingly mulling about. Then the scouts galloped back to Smith.

Based on the information his scouts had provided, Smith planned to launch a two-pronged attack against both ends of the village. At noon the following day, his army arrived in the proximity of the village. There Smith divided his command. But when the two forces charged in, they found the huts had been hastily deserted. Once again, the Indians had discovered the presence of the whites and disappeared into the wilderness.

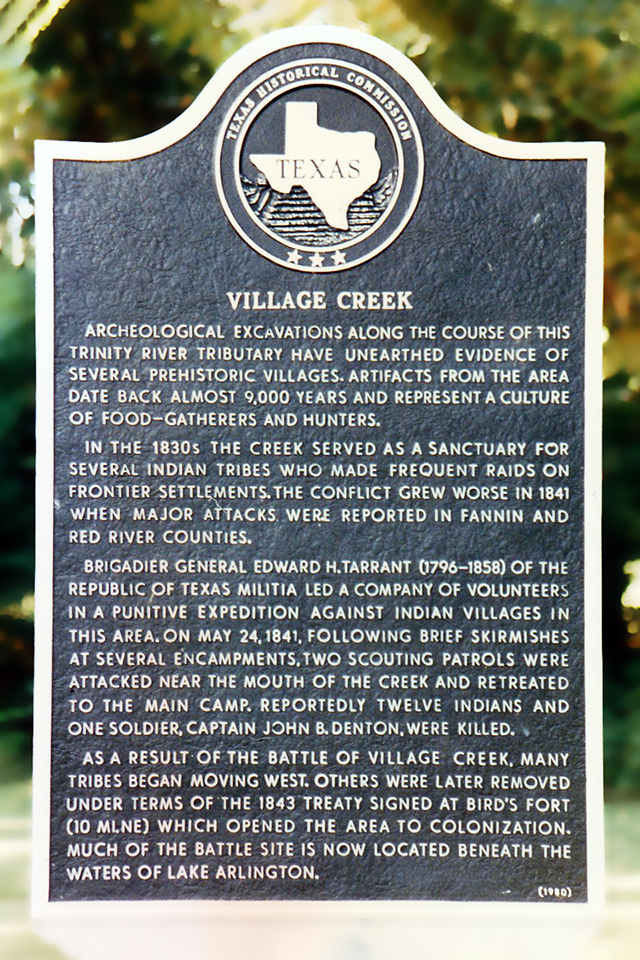

Perhaps because Tarrant's earlier Village Creek expedition had been the only campaign that had succeeded in locating and engaging an occupied Indian village in the forks of the Trinity, it is better remembered than the other military ventures into the region. Some sources have overlooked the earlier efforts and erroneously heralded Tarrant's rangers as the first Anglos to enter the upper Trinity wilderness.

However, the Village Creek fight hardly qualified as a major battle. Twelve enemy dead is a modest statistic, yet there were critics of the campaign who questioned if even that figure were not exaggerated in an attempt to glorify the endeavor. John Henry Brown described it as "fruitless" and "unfortunate." He wrote, "The expedition was unsuccessful in its chief objects and, from some cause, probably a division of responsibility, the men, or a portion of them, at the critical moment, were thrown into a degree of confusion bordering on panic."66

Joseph Carroll McConnell concurred, "Due to mismanagement, the whites had failed to draw the Indians into battle..."67 But if Porter's estimate of the size of the enemy can be believed, it was fortunate for the Texians that major battle had not developed.

However, the Village Creek fight should not be evaluated by the statistics, the number killed or not killed. More significant was the psychological impact on the tribes that inhabited the region. Tarrant's small force had succeeded where larger and better equipped armies had failed. And although the Indians had escaped Smith's force, they must have realized, perhaps for the first time, the vulnerability of their Trinity haven. For the protection of their homes and the safety of their women and children, many of the tribes migrated westward, to the Brazos and beyond. However, other Indians determinedly remained. The military expeditions to Village Creek had weakened, but not destroyed, the Indians' hold on the three forks of the Trinity.

Ultimately, the Village Creek fight was awarded an obscure form of immortality. At least three Texas counties were named for Texians who, among other deeds, participated in the battle.

The first of these, created in 1846, was Denton County. Death serves as a catalyst that a transforms men into heroes and heroes into legends. Captain John B. Denton became the martyr of Village Creek. His biographer, the Reverend William Allen, wrote, "He will sleep in an honored grave as do Fannin, Travis, Crockett and Bowie, and all that slumbering and moldering host who yielded their lives, shedding generously their patriotic blood for Texas."68

Denton's legend was both enhanced and distorted by prolific hack writer named Alfred W. Arrington, who had briefly known Denton. Arrington published a series of short stories loosely based on Denton's life, in which the protagonist was named Paul Denton. The stories endured long after Arrington's authorship was forgotten, the hero's name reverted back to John, and the events described sometimes became accepted as fact, often appearing in histories of Methodism.

Arrington originated the story, later accepted as fact, that young Denton had been adopted by "one of the most degraded families in Arkansas," and was both abused and neglected. In fact, Jacob Wells was generally regarded as a prominent figure in the Arkansas Territory. And while Denton apparently did not care for Mrs. Wells, there is no evidence that he ever suffered any mistreatment, other than an occasional "unbearable scolding."69

Another of Arrington' stories was the source of a dramatic, but fictitious, incident that was attributed to Denton. Denton and his wife separated after a quarrel, the story went. She took up residence in Fayetteville and found a job in a millinery shop. One night, shortly afterwards, she was forced to kill a man who had broken into her apartment. It was obviously self-defense, but she was a stranger in town and her assailant was a long-time resident. Indicted for murder, she was brought to trial. The judge asked her if she a had a lawyer. "No," she replied, "I have no attorney and no friends." At that moment, John Denton entered the courtroom and announced, "I will appear for the defendant, if acceptable to her and the court." With his oratory skills, Denton easily won both the case and a reconciliation.70

In time, Denton's legend transcended the Village Creek fight altogether. While pursuing Indian raiders, Arrington's Paul Denton was killed "not by the hand of the Indians, but by a shot from one of his own horsemen."71 Wilbarger described Denton's death with more accuracy in Indian Depredations in Texas (1889), but he did not identify the battle and incorrectly listed the year as 1839. There also were published accounts of Denton's death that either made no reference to the fight or which stated that Denton had been killed in revenge for the attack on Village Creek.72

In 1860, John S. Chisum, whose father, Claiborne, had fought at Village Creek, reportedly recovered Denton's remains and transferred them to the yard of the Chisum ranch house. In 1901, the alleged remains were again exhumed and reburied on the courthouse square in Denton.73

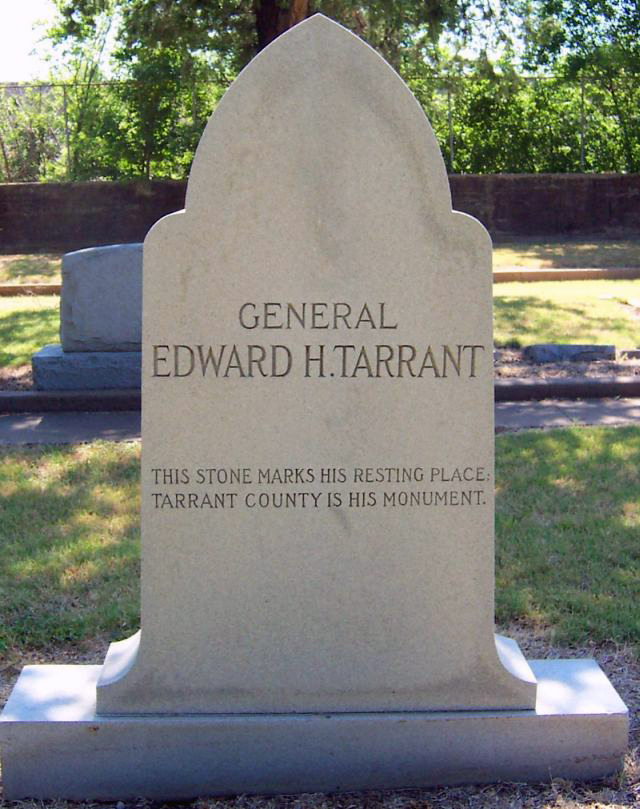

Nor was "Old Hurricane" forgotten. Tarrant County was created in 1849.

Young County, honoring William Cocke Young, was formed in 1856.

If Isaac Parker and Daniel Montague were actually at Village Creek, then two more counties can be added to the list. Parker County was created in 1855, and Montague County was formed two years later.

Some participants in the fight found greater fame elsewhere. On February 5, 1844, Sam Houston appointed William Cocke Young, the company's first lieutenant, to the post of district attorney for the Seventh Judicial District of the Republic of Texas. Young was a delegate from Red River to the Convention of 1845, and when the Mexican War began, he helped James Bourland raise a force of one thousand volunteers.

In 1851, Young moved to Shawneetown in Grayson County where he practiced law for six years and served one term as a U. S. marshal. However, he refused an 1854 appointment as land commissioner.

At the outbreak of the Civil War, Young was called to Montgomery, Alabama, to consult personally with Confederate President Jefferson Davis. He returned to Texas to organize and command the 11th Texas Regiment of Cavalry. He led his command into the Indian Territory and captured forts Arbuckle, Wichita, and Cobb. Young was assassinated by border scavengers on October 16, 1862. His murder prompted a mass hanging of abolitionists in Gainesville.

James Bourland, the man originally elected to lead the company, was appointed collector of customs for the Red River district in February, 1842, a position he held for five or six years. Bourland was elected to the Senate of the First and Second Legislatures, representing a district that included Bowie, Fannin, Lamar, and Red River counties. During the Civil War, he organized a regiment of men that he placed along the Red River to protect the Texas border. Bourland died in 1868.

His brother, William, had an equally successful career. He represented Lamar County in the Eighth and Ninth Congresses (1843-1845) and then served as a major in the Mexican War. Afterwards, he again represented Lamar County in the First and Second Legislatures and Grayson County in the Fifth Legislature. He died just prior to the Civil War.

General Tarrant retained his interest in the forks of the Trinity. He authorized Major Jonathan Bird "to raise a company of volunteers in the Sumer (sic) of 1841 to go on the Trinity and establish a fort and maintain that position."74 Several veterans of the Village Creek fight volunteered for Bird's company: William Claiborne Chisum, Mabel Gilbert, Samuel Moss, and Captain Alexander Webb. Wade Hampton Rattan, who may have fought at Village Creek, served as Bird's quartermaster and secretary. Bird established his fort that December, on the Trinity just north of Village Creek. Rattan became its first casualty, ambushed by hostile Indians.

Bird's Fort, the first white settlement in what would become Tarrant County, failed after only a few months. Mabel Gilbert, the former steamboat captain, fabricated two cottonwood dugouts and paddled his family down the Trinity to join John Neely Bryan's new settlement on the Elm Fork. Gilbert may have been the first white man to navigate the forks of the Trinity. His wife, Charity, became the first white woman in the new settlement.

Mrs. Gilbert also has been credited with naming Bryan's settlement. However, there is considerable debate about whom she was honoring. Most sources cite United States vice-president George Mifflin Dallas.

In December of 1841, as Bird was establishing his ill-fated fort, Sam Houston assumed the office of President of the Republic of Texas for a second term. During his second administration, Houston found the people of Texas more receptive to his efforts at constructing a peace with the Indians. Anglos who had once supported Lamar's policy of Indian extermination had finally grown weary of the endless bloodletting. Others were simply pragmatic. The war had depleted the treasury, and there was scarcely enough money left to adequately support battalions for the defense of the frontier.75

The emigrant tribes, those that had survived Lamar's war of extinction, also displayed a willingness to negotiate. Expeditions such as General Tarrant's Village Creek raid had proven that their villages were vulnerable to sudden attack. There was no longer any refuge in Texas where they could safely hide from the whites.

Finally supported by a sympathetic Congress, at least on the Indian issue, Houston invited the Texas tribes to attend a peace council. On March 31, 1843, representatives from the Anadarko, Caddo, Delaware, Hainai, Kichai, Shawnee, Tawakoni, Waco, and Wichita tribes assembled at Tehuacana Creek, about eight miles from present day Waco. The Indians unanimously agreed to a cessation of hostilities. They also promised to attend a grand council, a scheduled for August 10—the full moon—where they would enter into a lasting treaty with the Republic of Texas.

For the site of the grand council, Houston proposed Jonathan Bird's abandoned fort in the forks of the Trinity.

On July 6, Houston appointed two commissioners to go to the fort and assist with the negotiations. One of the new commissioners was an old friend. George Whitfield Terrell was born in Nelson County, Kentucky in 1803, but his family had soon migrated to Tennessee. He was admitted to the bar in 1827, and the next year he was appointed district attorney by then governor of Tennessee, Sam Houston. From 1829 until 1836, Terrell served in the Tennessee Legislature. He came to Texas the following year. During Lamar's administration, he was appointed district attorney of San Augustine County, where he also served as district judge. During a period when Lamar had fallen ill and David G. Burnet temporarily had functioned as President, Terrell was selected secretary of state. In December, 1841, Houston appointed Terrell attorney general of Texas. A prominent and capable leader, Terrell had already served as an Indian commissioner and had assisted in the council at Tehuacana Creek.

For the second commissioner at the Bird's Fort council, Houston designated General Edward H. Tarrant.

It was an awkward moment for "Old Hurricane" to be out in the wilderness. The Republic had authorized the formation of six new companies for frontier defense, the force to be organized and commanded by a major general elected by popular vote. In June, while Tarrant was in Austin receiving his license to practice law before the Texas Supreme Court, he had declared his candidacy for the post. And because he did not believe in holding one office while seeking another, he had resigned his commission as Brigadier General of the Fourth Brigade.

Strong competition existed for the new post. Among the other candidates were such prominent figures as Memucan Hunt, Sidney Sherman, and Alexander Somervell.

The election would be held in September. To effectively challenge such formidable opposition, Tarrant desperately needed time to ride the campaign trail. Instead, he laid his political ambitions aside and rode back to the forks of the Trinity.

In the days prior to the full moon, Tarrant and Terrell greeted the chiefs and other Indians who assembled at Bird's abandoned stockade. The Indians represented from ten native and emigrant tribes; the Anadarko, the Biloxi, the Caddo, the Cherokee, the Chickasaw, the Delaware, the Ioni, the Keechi, the Tawakoni, and the Waco.

The Great White Chief Houston arrived just before August 10. However, he postponed the council for several days, hoping the Comanche would also appear. When they did not, Houston assembled the tribal representatives around a council fire. He appeared before them bedecked in a suit of purple velvet. An Indian blanket thrown over his shoulder reminded them that he was a blood brother to the red man. A massive Bowie knife thrust into his belt symbolized his prowess as both hunter and warrior.

Houston addressed the Indian representatives:

We are willing to make a line with you, beyond which our people will not hunt. Then in red man's land beyond the treaty line unmolested by white men, the hunter can kill the buffaloes and the squaws can make corn.76

The president explained that he must return to his people. He would leave Tarrant and Terrell to conclude the negotiations. They would speak Houston's words. The Indians were to regard the commissioners as they would the Great White Chief himself.

Tarrant and Terrell finalized the treaty with the assembled tribal chiefs. First, they all agreed to an immediate cessation of all hostilities.

The Texas government would appoint licensed Indian agents to man trading posts along Houston's line of demarcation (which stretched from the forks of the Trinity southwest past Comanche Peak to the San Saba ruins and then southeast to San Antonio). These agents would hear the Indians' complaints, help maintain justice, and communicate the orders and wishes of the president to the tribes. No one, red or white, would be allowed to cross the line of trading houses without permission from the president.77

Both factions also agreed to surrender all their prisoners. In accordance with this provision, "Old Hurricane" brought forth the Indian child he had taken at Village Creek and returned it to its people. This act may have been emotionally difficult for Tarrant, for tradition maintains that he and his wife had raised the child for the two years since the Village Creek fight.

"Old Hurricane," the warrior, had become a peacemaker.

The Bird's Fort treaty, containing twenty-four articles, was concluded and signed on September 29, 1843. The Texas Senate ratified the treaty on January 31, 1844, and three days later Sam Houston affixed the Seal of the Republic to the document, passing it into law.

The Bird's Fort treaty ranks as the most significant treaty signed between the Indian tribes and the Republic of Texas. It established both a precedent and a pattern for all subsequent treaties, including the one signed with the Comanches.

In the years following the treaty, Tarrant continued career in public service. In September, 1845, he represented Bowie County at a convention in Austin considering statehood for Texas.

Tarrant moved to Navarro County the following year and became Chief Justice of the county. He represented both Navarro and Limestone Counties in the Third and Fourth Texas Legislatures.