Lost to History

Not much remains today of a century-old home near campus where outcast girls once found refuge. Everything you need to know about the Berachah Industrial Home for the Redemption of Erring Girls you can find in the weeds. That’s nearly all that remains of what was once a proud, ocen controversial rehabilitation center for outcast teen-aged girls that stood a century ago in what’s now Doug Russell Park.

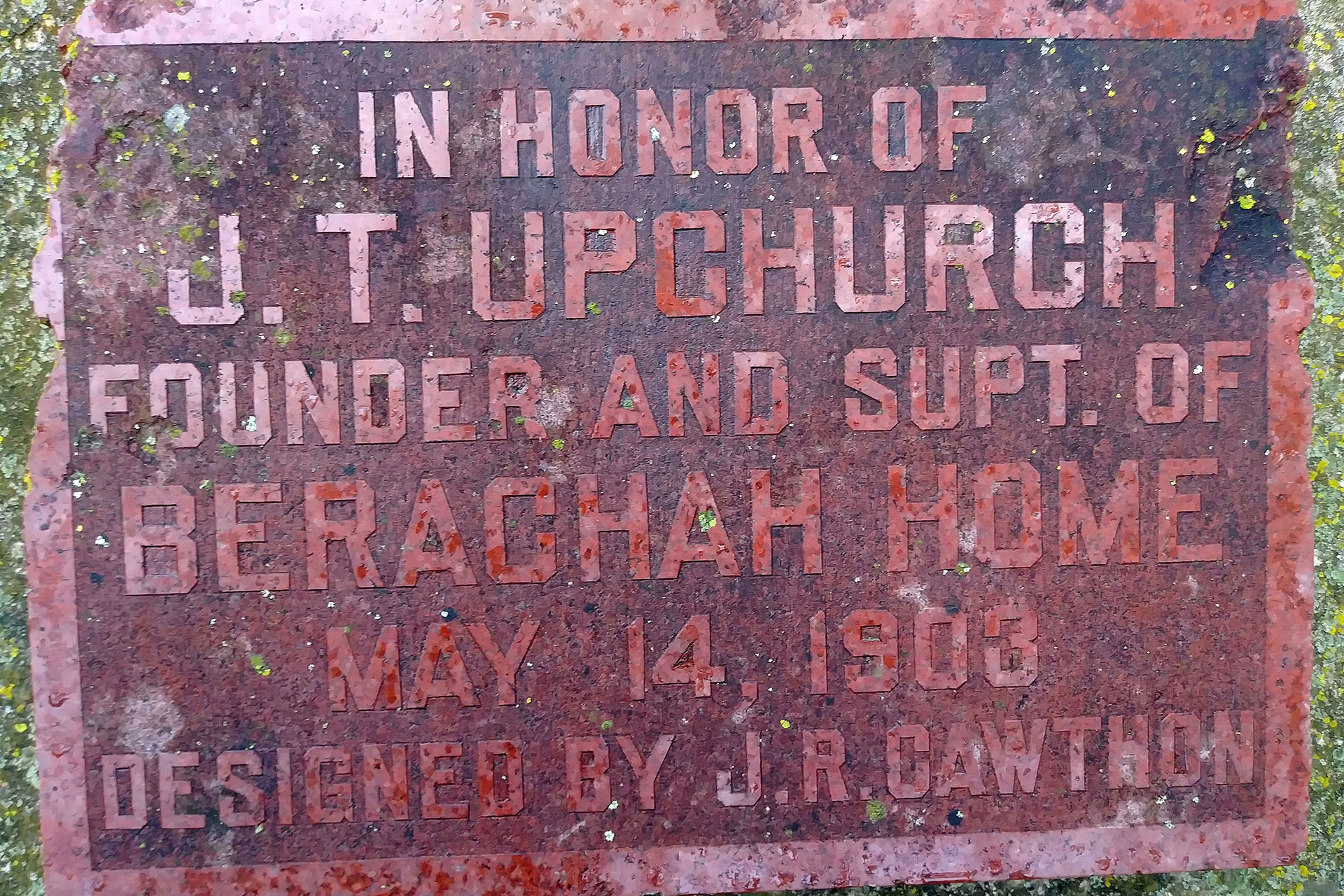

Lost in the overgrowth, a rusty wire fence bends groundward. In these weeds grow oak trees that have seen shamed women come and go, babies born and babies die. These weeds have closed in on an unusual history. But the last piece of the Berachah Home has been reclaimed from them—a cemetery in a clearing southwest of Davis Hall. A pristine cyclone fence restrains the choking thicket and sun-faded beer cans. It’s impossible to tell who’s in most of the 78 graves: Infant No. 15. George. Twins No. 6. Some, probably, died in influenza or, later, measles epidemics. Most were buried between 1904 and 1935. This is what’s left of the Rev. James Tony Upchurch’s answer to what he called the “white slave trade.”

Exactly a century ago—in 1903—Upchurch, a diminutive, mop-headed Church of the Nazarene preacher, founded the home on what’s now UTA’s property to redeem young women society saw as lost. Centennial Courts apartments stand on part of the acreage now. Any remaining photographs or documents are kept in four boxes in the Central Library’s Special Collections.

Berachah, you should know, is Hebrew for blessing: “They assembled in the valley of Berachah and there they blessed the Lord. Therefore, the name of the same place hath been called the valley of Berachah to this day.” (II Chronicles 20:26) Upchurch found his valley of blessing in an oak-clustered lot where, he later wrote, he “felt the presence of God, who gave an unmistakable promise that this was the place.” It was ideal, far from big-city temptations and the women’s old lives. The Berachah Home went up on the knoll just south of town. Upchurch called the spot Rescue Hill.

Planting Roots

The first pregnant girl to move in was Dilly. Her baby boy, Alpha, stayed at the home through infancy, evidently reared by the campus matron. Dilly’s whereabouts, like most of the residents here, are lost to history. Thousands passed through the home before its abandonment on the first day of 1935. The only thing most had in common was that they had nowhere else to turn. If a resident gave birth, she couldn’t offer her baby for adoption because Upchurch believed it wrong to separate a mother and child. On May 2, 1919, he and his wife even traveled to Oklahoma to bring to Berachah the daughter of a resident.

Pregnancy was not a requirement to live here. Applications were submitted by relatives or clergy for “wild girls,” for heroin addicts, for young widows who couldn’t support themselves. They came from other states, too, since Upchurch advertised on [the] radio. “He was really ahead of his time,” said Bill Pattilos, 80, a great-nephew of Upchurch. Pattillos’ grandmother, the reverend’s sister, is buried in the cemetery.

To accommodate a growing population, the Berachah campus eventually expanded to 67 acres and encompassed 10 buildings, functioning as a tiny, self-sufficient city with its own hospital, school, livestock barn, and chapel. In the printshop, staff and residents produced The Purity Journal, a magazine-style newspaper that grew to national circulation.

Upchurch’s granddaughter, Dorothy Betts, recalled that the property was “beautiful and well-kept.” She grew up near Berachah and often went there to visit and play. She still lives in Arlington [i.e., in 2003]. “And the girls there were happy,” she said. “They had something to do, and it was something they liked to do. They worked in the area they liked to work. We had some very good artists, and their pictures would hang throughout the buildings in the home. If they liked to cook, they could do that.” The core of the place—and why it was called an “industrial home”—was its workshops. Before they could leave, girls learned printing, nursing, stenography, sewing, gardening or home economics. Ideally, that eased them back into mainstream society.

Tenants, sometimes called inmates, lived rent-free, provided they abided by Upchurch’s few rules: no eating pork, no drinking coffee or tea, no tobacco, and no telephone on Sundays. The reverend often claimed that 75 percent of those in his care left as “upright girls,” though that could have been fund-raising ballyhoo. Berachah’s existence relied solely on donations; it was the only institute in Texas for girls that was entirely supported by charity. Upchurch, who annually earned a comfortable $5,000 [over $98,000 in 2020] plus expenses, proved an effective peddler. In 1932, at the height of the Depression, the home received $33,761.93 in donations [more than $664,000 in 2020]. The girls also earned money selling [the] handkerchiefs they made. “He was at least recognizing the need,” said Geraldine Mills of the Arlington Historical Society. “I’m sure he didn’t get rich off handkerchiefs.”

Upchurch was a stirring speaker, too, often going [on] for hours. He had plenty to tell. Like the story of a 16-year-old from New Mexico who would bear the Portales County sheriff’s baby. Or 18-month-old Rosemary, whose mother, Dorothy, died during childbirth. (A Weatherford couple adopted Rosemary, and Upchurch took her there.) Typical, too, was the story of Bessie Mae Osborn from Dublin, Texas. A logbook entry on June 25, 1925 says, “Rev. D.C. Gafford made an application for girl [Osborn] 17 years of age, diseased, whose father threatened to kill her.” What Upchurch likely didn’t share with donors was that Osborn was accepted, then promptly ran away. More commonly, girls loved life there. Many never left, and others went away and returned. Some married in Berachah’s chapel as adults.

In God They Trust

Townsfolk didn’t share the girls’ love of Berachah. While no evidence was found of threats or violence against the home, Betts remembers a strong division between Berachah and Arlington. “That’s the reason they had their own home,” she said. “I never felt any rejection or anything, but the girls were not very well-received. It was just an attitude thing, I think.” Citizens accepted, however, fifth-graders attending the Berachah school when the town’s southside school burned in the early 1930s.

Upchurch’s own family was divided on his work. Pattillos said his father, a Presbyterian minister, had little to do with the Upchurch side of the family. Even Upchurch’s wife didn’t always see things his way. Though her husband was a devout Nazarene, Maggie Mae Upchurch remained a Methodist. “The churches had a different philosophy on what to do with these babies,” Betts said. “My grandmother agreed with him on that, but not enough to switch religions. The Upchurches attended the Nazarene church at Berachah on Sunday mornings but would go to the town’s Methodist church at night. And always, they shared their faith with the girls in the home.

A story in The Purity Journal tells of Ollie Burns and how she became the first girl to find the Lord. She was expected, then, to act as a missionary for the home, which she did for the next five years until she died at 21. The Berachah Home was officially nondenominational—it accepted donations from people of all faiths—but religion was emphasized. The girls were to attend chapel regularly, and the register indicated when someone moved out, whether she had been saved. More than once a girl’s profession of faith is noted, only to have a different handwriting indicate that she never really converted. Huge tent revivals at the home were conducted under large signs urging attendees to trust in God, abstain from tobacco and pray for the girls.

Mainly because of such church support, Berachah could house 170 girls in 1932. To keep up with the need, Upchurch more than once annexed land around his campus. Ultimately, that nearly caused trouble. On March 31, 1942, the Arlington school district sued, claiming that the home owed more than $1,200 in property taxes [over $18,300 in 2020 dollars]. Attorney Albert Miller said in the lawsuit that Upchurch was guilty of fraud in an elaborate real estate scheme. A county judge dismissed the case in May and held Miller in contempt. His remarks were struck from the record. Two years later the school district lost an appeal and was ordered to cover all unpaid court costs. Audits conducted before the suit suggested that Berachah’s books were legitimate but somewhat disorderly.

In ensuing years, so was the property. The Arlington Historical Society’s Mills remembers the last structure standing, a one-room chapel with a regally arched doorway and a woodburning fireplace. Adjacent to the cemetery, it was a place for solitary prayer. “It was so small, maybe six people could have sat down,” she said. “It sat there for a long time before UTA tore it down because kids were hanging out in there and drinking beer and starting fires.” Now you’ll find the outlines of its foundation, with a few bricks still in place, and nothing more. “They should have saved it,” Mills said. “I remember once I found it during Girl Scouts, and I thought I was Nancy Drew all over again.”

Berachah was all but forgotten almost as quickly as it closed. When Pattillos, who now [2003] lives in Sacramento, Calif., attended North Texas Agricultural College (now UTA) in the early 1940s, he had no idea what was across Cooper Street. “I went to school there. And I didn’t even realize my grandmother was buried there,” he said. “There just wasn’t much over there.” Sixty years later, nothing has changed. Mills wishes it would. She would like to see the School of Architecture reconstruct some of the old Berachah buildings.

As for the history, that’s a different story.