Former Slaves on the Middleton Tate Johnson Plantation Speak (Part 1 of 2)

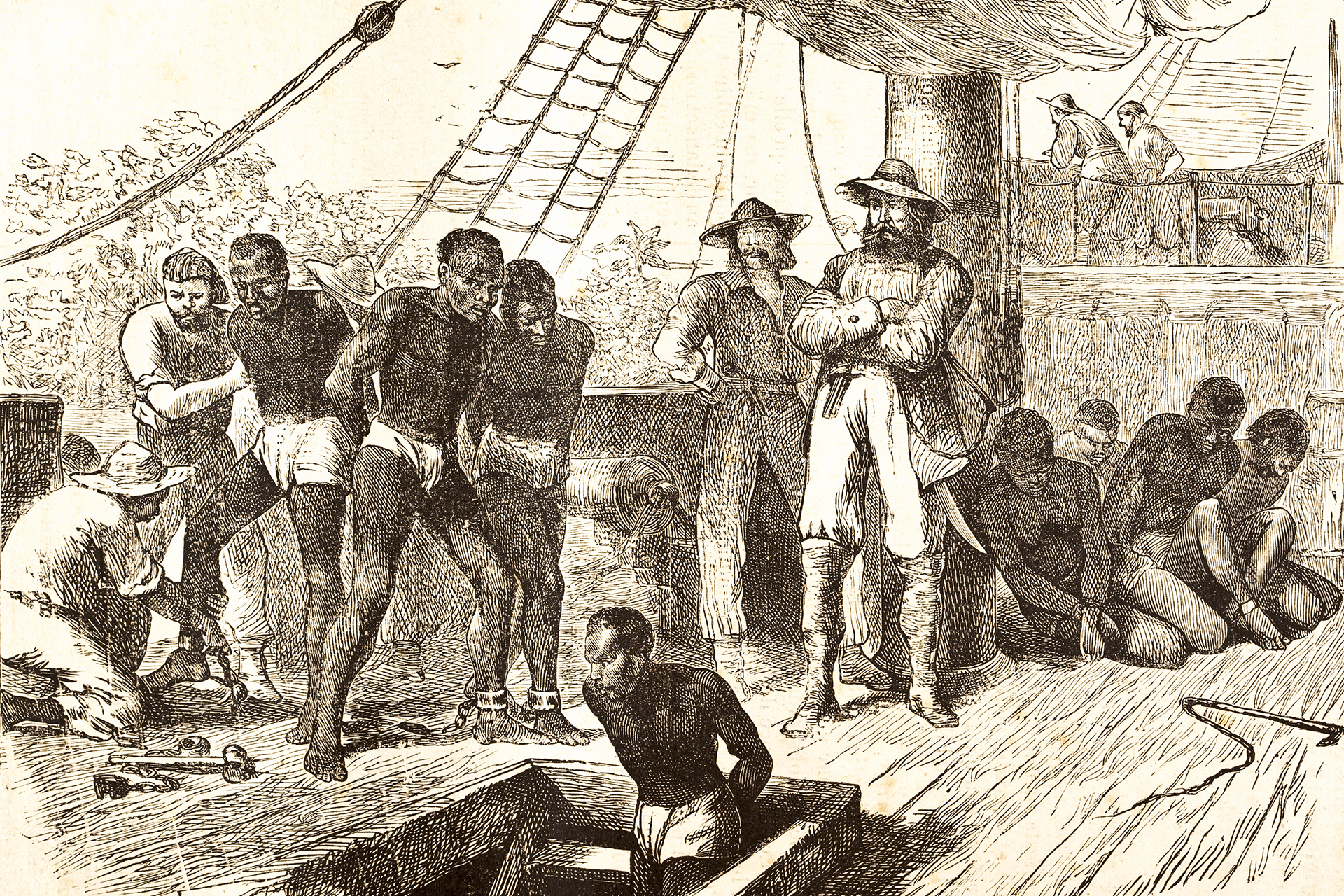

In 1997 the Fort Worth Museum of Science and History had its first major exhibition devoted to the Trans-Atlantic slave trade - A Slave Ship Speaks: The Wreck of the Henrietta Marie exhibit describes the slave trade circuit and its cargo.

As part of this exhibit, Gayle W. Hanson, historian and Arlington resident, had the pleasure of working with the Fort Worth Museum of Science and History in developing local history exhibit information with regard to slavery to complement the national traveling exhibit. Research information for the local history exhibit came from the American Slaves Narratives portion of the Federal Writers' Project, which was a part of the Works Progress Administration (WPA).

Gayle noted that "These autobiographical accounts of former slaves stand as one of the most enduring and noteworthy achievements of the WPA. Compiled in seventeen states during the years 1936-38, these accounts are interviews with former slaves, most of them first-person accounts of slave life and the respondents' own reactions to bondage. The interviews afforded aged ex-slaves an opportunity to give their personal accounts of life in those days."

"It was a wonderful discovery to find typescript copies of Tarrant County’s slave narratives at The University of Texas at Arlington, Special Collections (just ask for WPA Federal Writers’ Project-Fort Worth City Guide Records), as well as at the Fort Worth Public Library. I have researched this subject for many years and have located some descendants of these narratives."

But first, before we get to the first of the three Slave Narratives, following is some background on Middleton Tate Johnson (from the Handbook of Texas Online):

“JOHNSON, MIDDLETON TATE (1810–1866). Middleton Tate Johnson, ranger and politician, was born in 1810 in the Spartanburg district of South Carolina and moved to Georgia at an early age. He won election in 1832 to the lower house of the Alabama legislature, where he served four successive terms. In 1839 he and his wife, Vienna, moved to Shelby County, Texas. There Johnson secured an immigrant's headright of 640 acres in what is now Tarrant County. He served in the Regulator-Moderator War of 1842–44 as a captain of the Regulators. In the final days of this conflict he represented his county in the Congress of the Republic of Texas and served for a short while in the Senate. In 1845 he raised a company of volunteers, mostly former Regulators, and served in Col. George Tyler Wood's Second Regiment, Texas Mounted Volunteers, at Monterrey. He was discharged on October 2, 1846, and returned to Texas, where he raised a mounted company that became Col. Peter H. Bell's ranger regiment, which served on the northern frontier. Johnson, as lieutenant colonel of the unit, served near the trading post at Marrow Bone Spring, at the site of present Arlington. On June 6, 1849, he and brevet major Ripley A. Arnold established a fort and army outpost at the junction of the Clear Fork and the West Fork of the Trinity River. They named it Fort Worth in honor of Gen. William J. Worth. Johnson also helped to organize Tarrant County.

For his service in the Mexican War he received a grant of land now in Tarrant County. He settled his family (three sons and five daughters) in 1848 near Marrow Bone Spring [now a linear park at 600 W. Arkansas Lane, just east of Matlock Rd.; the spring is part of the creek now known as Johnson Creek], where he established a cotton plantation. He soon became one of the wealthiest and most influential men in the region; he is reported to have owned the largest number of slaves among Tarrant County planters. The settlement surrounding his home became known as Johnson Station [I would have said that the trading post and stagecoach stop established by M.T. Johnson became known as Johnson Station]. Johnson worked to secure a railroad route west of Fort Worth and helped Gen. Thomas J. Rusk survey the proposed Southern Pacific line to El Paso. In the state election of 1849 he failed in his bid for the lieutenant governorship. In 1851, 1853, 1855, and 1857, he unsuccessfully ran as a Democrat for governor. In 1859 he bolted from the party and supported Sam Houston. Johnson returned to the Texas Rangers in 1860 to lead a regiment against the Comanches in a much criticized and largely useless campaign. During this time, after the death of his first wife, he left his command to travel to Galveston to marry Mary Louisa Givens. Because of this apparent dereliction of duty and the lack of results from his campaign he was widely censured. In 1861 he donated land for the courthouse in Fort Worth.

Although opposed to secession, Johnson served in the Secession Convention. For the Confederacy he raised the Fourteenth Texas Cavalry Regiment, which served on both sides of the Mississippi. He was regimental commander until he was succeeded by John L. Camp. Johnson also supervised a blockade-running system to bring supplies into the Confederacy. In the course of the war his oldest son, Tom, was killed, and his second son, Ben, died of consumption. After the war Johnson returned to politics. He was elected to the state Reconstruction convention in December 1865. On May 15, 1866, while returning to Johnson Station, he suffered a stroke and died. He was first buried in the State Cemetery, then reinterred near his sons in the family cemetery, now in Arlington [on Arkansas Lane, just east of Matlock Rd., across from Marrow Bone Spring Park]. Johnson was a Mason. Johnson County was named in his honor.”

The following comments were recorded at the time of the interview of former slave Hannah Mullins (c. 1937) by Sheldon P. Gauthier, who was the interviewer.

"Hannah Mullins, 81, was born on former Gov. M.T. Johnson's plantation, which was located at Johnson Station, Tarrant County, Texas. Her mother was used as a mid-wife and child nurse, and Hannah was told to stay with the Johnson children and do whatever they asked. Since the Johnson children were good to her and didn't abuse her, she played with them as one of the family until after freedom, when she stayed with her own parents.

A good example of a slave's loyalty was shown when Hannah's father went to Austin, to dig Gov. Johnson's body from his grave [in the State Cemetery], haul it to Arlington, Texas, where the family would bury him in the family cemetery. Hannah's parents remained on the plantation until their deaths, but she married William Mullins when she was 16, and they established a home of their own on the Johnson Plantation. After three children were born to them, they moved to Arlington, Texas, where Bill was employed by a livery stable. A few years later, they moved again to Fort Worth, where Bill was employed at common labor until his death in 1935. Hannah went to live with her daughter at 1820 Chambers Avenue, Fort Worth, Texas, after his death. Her sole support now is a monthly $9.00 pension received from the State of Texas."

The Narrative Provided by Former Slave Hannah Mullins

Ise bo'n on Cunnul M.T. Johnson's plantation at Johnson Station, Tarrant County, Texas. The time was a little over 81 yeahs ago, and Ise been told 'twas on June the 19th. Ifn that's so, sho was a powerful lotta folks that celebrates my birthday, 'long with the Mancipation Day doin's.

Twas like a little city, what with the buildings and all that was on the plantation. Ise fails to recall the number of slaves MarsterJohnson have but I sere members that each family have a double log house. That is, there was two rooms separated by a hall twixt them, and the houses were in rows like a city. Then Marster have the shoe shop where the hide tannin' was done, and the blacksmith shop, the ginmill, and soon there was the spinnin' room where the cotton and wool was spun into thread, and the looms where the thread was run into cloth so's the seamstresses can make the clothes and so on. Marster Johnson's plantation was selfs'portin, far's Ise knows, and raises the cotton to make the money crop.

The other crops was small 'cordin to the cotton, but 'twas enough to raise vegetables and so on fo food. Each family gits theys rations on Sunday mo'nin aftah the bell rings, and tooks the rations to they own cabins, where the women folks cooksit when needed. If the family have good workers in it, it was give a cow and hawgs to raise. We all has chicken once in awhile, but the Marster keeps the chickens in a bunch together.

Co'se now, Ise a kid on the plantation but Ise know what it's all about 'cause freedom nevah changed things much 'round there. Ise raised in the nursery 'til Ise 'bout five yeahs old. The nursery was where the mammies brings theys babies til they can git 'em back aftah workin hours. This nursery was work a-plenty fo' the womens that runs it 'cause they are s'posed to keep the kids out of fights. 'Twas a big job 'cause the kids will fight evah time the womens have theys backs turned. The real trouble comes when meal time comes around. Twas several long wood troughs put on the table, and each kid was give a wood spoon. Usually, the trough had milk with corn bread crumblin's in it, and the kids are lined up and down the table. The nurse gives the word when to eat, and the kids all tries to git mo'ren the rest of them. That starts the a'guments and the fights all over. The nursery also has slides fo' to play 'round and several sand boxes. Marster Johnson was sho good to all the little kids.

My mammy was the mid-wife fo' the whole place. She was sorta hunch-back and not able to work good, but was at mid-wifin', so Marster sets her to that and carin' fo' the little piccaninnies 'til theys able to be in the nursery with the rest of the kids. Mammy mid-wifed fo' ole Mistez too.

Ole 'Mistez have four to five chilluns, and aftah Ise five yeahs ol', Ise took out to stay with Themas the nurse. Twarnt any nursin' to be done but I sejus' to do what they wants me to do, like gwine aftah watah, helpin' dress, and so on. The Johnson kids could have made it hard fo' me but theys good to me, and we all plays together like Ise white as they is. Ise fed the same vittals and wears the same clothes as they does. Have the same sleepin' time and all.

Co'se now, Ise fails to recollect the games we all played, but the Johnson kids were house kids and don't want to be all the time a -runnin' round, so 'twas easy fo 'me. I seall the time wantin' to go to the field and work with my pappy, but Mistez Kate Johnson won't let me 'cause she wants me to stay with the kids. 'Twas the best fo' me, but Ise guess Ise bo'n to be a plow hand 'cause that's what Ise all the time wantin' to do.

Ise don't know nothin bout when freedom comes but Ise knows the time 'cause my pappy comes aftah me, and we all lives together in the cabin 'instead of mea-livin in the Marster's house with the kids.

Pappy and mammy goes on a-workin' fo' Marster as the field hands on wages 'cause we nevah share crops while we was a-livin at Johnson Station. Ise gits plenty a-plowin' to do aftah Ise goes to live with my mammy and pappy. Many's the time Ise aplowin in the field and the sleet was fallin' all around us. Ise done something 'long about that time that Ise could nevah do. All the time Ise at Johnson Station, Ise never had shoes on my feet 'cept when we goes to church, and we nevah goes to church til aftah freedom 'cause 'twarnt no churches fo' the cullud folks in slavery times. Ise 'spect ifn youse was to go 'round barefooted, that youse would ketch youse death of cold. 'Twarnt nothin' to us 'cause thats the way 'twas all the time. We nevah puts the shoes on gwine to church 'til we are several hundred feet away, then puts 'em on. 'Twas done that away fo' to save the shoes.

Aftah freedom comes, de Klux goes to a-runnin around over the country and causin' the cullud folks plenty a-trouble. Ise see the PatterRollers befo' freedom, but de Klux comes right up to where we lives to git people. They goes around over the country in bunches on hoss-back. My mammy was a-ridin her mule down the road towards home aftah mid-wifin' fo' some cullud folks, and a bunch comes down the road aftah her. Mammy moves over so they can git past without any bother, but aftah they was apassin', one of them hollers, halt!' The other mens says, 'Dat's Emma. She's alright, and they rides on without any trouble.

The other trouble was when the Klux was a-tryin' to shoot Martha Ditto's husband. 'Stead of shootin' him, one of the shots goes a-strayin 'and kills the baby in Martha's arms. The Klux kinda thinned out aftah that and 'twarnt much trouble.